A place to see from

...and the result of actions taken

For this month's etymological excursion, I've decided to have a look at the two most common terms used to describe our field: Theatre and Drama. Synonyms? Antonyms? Chicken and egg? Despite being the words most likely to be included in our job description, do we really know what the difference is? Is there a difference?

People train in drama schools in order to work in the theatre sector.

Some young people go to a theatre school or Youth Theatre as a hobby.

A dramatist is someone who write plays but it is a theatre company that stages them.

In high school there may be (should be!) a drama department led by a drama teacher who might put on performances in a studio theatre which might be called the drama studio (a few may even have the fortune of a school theatre or three).

An expert in the drama of the Spanish renaissance will spend a lot of time reading plays.

A drama therapist might never touch a script.

We might be told someone is dramatic or theatrical, but are these the same?

Going out to the theatre sounds like a treat; being rushed into one quite the opposite.

When asked if we know anything about the drama at the local theatre last week, do we prepare to tap into our mental repository of theatre history or point out that the DSM losing it and decking the director with her prompt copy was always going to happen?

Even allowing for the blurring of common usage, there is certainly room for confusion here. And yet, even if you had never really considered the difference before, there's a good chance you probably have an intuition that one is to do with performance (theatre) and the other with process or content (drama). Is it as simple as that?

A place to see from

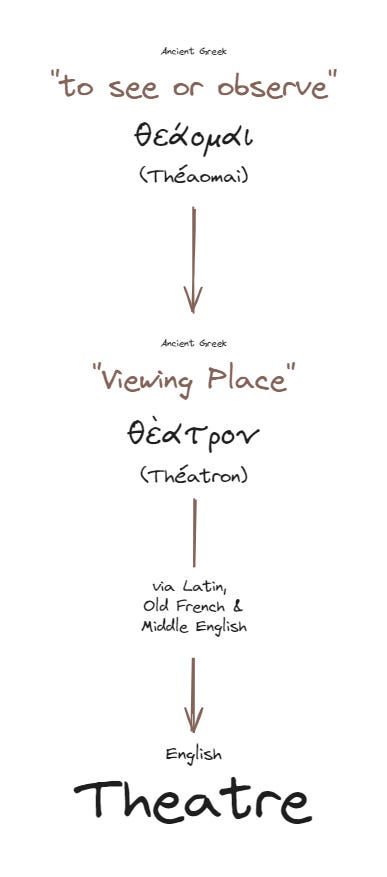

Theatre, as a term, has its roots in the Ancient Greek θέατρον (théatron) - a place for viewing, which in turn comes from θεάομαι (theáomai) - to see or observe.

The seats built into the south slopes of the Acropolis in Athens are the 'théatron' - the place to watch the events on stage. Likewise, when the only route to becoming a surgeon was to observe surgery in action steeply tiered seats were added to create 'operating theatres'. The 'theatre' in this sense is a physical space.

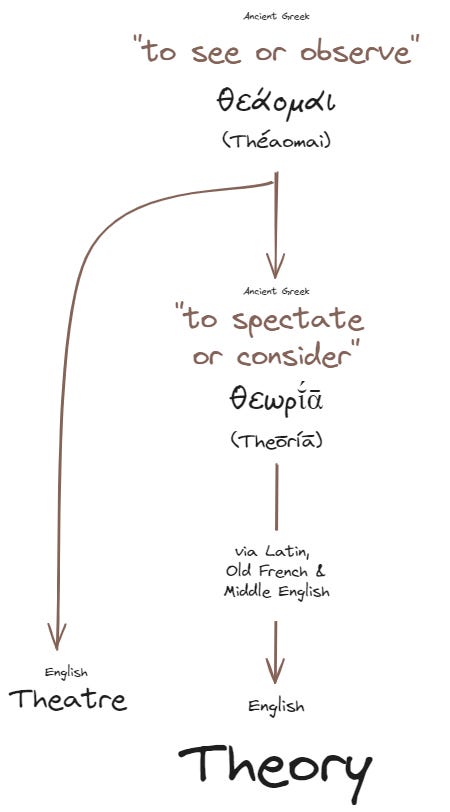

With so many English words tracking back to Ancient Greek it is sometimes worth looking for other words in current usage that have derived from the same root.

That “theory” comes from the same etymological root as theatre is perhaps not surprising. If I were to describe an activity that involves the prediction of what might happen IF a certain set of actions occur, in a certain context, within a specific period of time, would I be talking about theory or theatre?

From another perspective, consider the prevalence of spatial/visual metaphors used when we hypothesize the future or reflect on the past. We talk about 'from his position', 'my point of view' or 'where we stand'. We inquire about someone's angle, the stance they took, and hope they can see things from both sides1. With this in mind the 'viewing place' of Theatre might offer not just a physical location that makes it easier to see the stage, but also a metaphorical platform from which to 'theorise', to spectate and consider, the result of actions in the world.

The result of actions taken

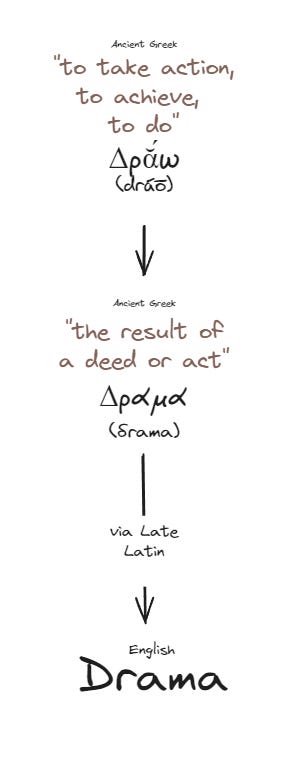

Drama comes to us more or less unchanged from the Ancient Greek, Δρᾶμᾰ (drâma) - the result of a deed or act. The term was used to distinguish staged performance from the monologue forms of spoken narrative (Epic) and first person verse (Lyric). The word is rooted in Δράω (dráō) - to take action/to do, which itself may well stretch back to Proto Indo European.

Drama could be said, then, to consist of deeds and the actions that result from them. Epic form, conversely, describes the action, whilst Lyrical externalises internal responses to action.

So, yes, the instinct to relate Drama to content is correct, as is the sense that connects drama to process. However, the content referred to is not the written script but the pattern of actions, the 'doings' that occur between human 'beings' recorded in the text. Equally, the drama process is not the games or exercises but the actions and response to actions imagined and reformulated through the activities.

Thus:

a dramatist codifies action into text - though the action is seen at a theatre

dramaturgy considers, or curates, the content (action?) of a performance.

drama school is a place to learn how to realise deeds and actions in performance, but it is a theatre company that co-ordinates the circumstances in which the action is seen.

at a youth drama workshop you would expect to create and experiment with actions and the results of actions, though there will be no formal viewing of this work (as there would be with at a youth theatre)

Ok, apart from sounding like I swallowed a dictionary, how is this useful?

As I've said previously, these jaunts into etymology are not motivated by linguistic puritanism and of course there are exceptions to the usage I've described. Language is constantly evolving, and meaning sits far more reliably alongside the intention of the person saying the word than a record of its use two and half thousand years ago. Digging into the word is really just an excuse to find useful insights.

Neither should we get locked into specific contexts. Each culture evolves its own terms to describe the art it produces. Whilst the distinction between theatre and drama articulated here is fairly consistent among languages with Proto-Indo-European roots, subtle, and not so subtle, divergences occur in the terminology of other linguistic traditions. Each of these is in itself an opportunity, or excuse, to give conventional assumptions about our work a bit of a shake up.

At a very basic level the differences explored above are helpful when considering, for instance, why TIE is Theatre in Education and DIE is Drama in Education. More than once I've encountered problems with projects where one person in the team has unknowingly got the two terms mixed up. All manner of misunderstandings and resulting entrenchment could have been avoided had the difference been clearly articulated.

More useful perhaps is the degree to which getting underneath the words we use helps to counter reductionism. That theatre might be a place to theorise about life, that drama is, not about emotional outpouring, but an arena of human action encountering human action, these are ideas that feed the imagination and generate possibilities.

Sources:

Hornblower, S., Spawforth, A. and Eidinow, E., 2012. The Oxford classical dictionary. 4th edition ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Onions, C.T. ed., 1996. The Oxford dictionary of English etymology. Repr ed. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Perhaps we evolved spatial reasoning first, adding social and then abstract thinking later? I'm planning to come to this in another post!