Did Someone Explain The Rules?

Principles to avoid it all kicking off #3

This is the third newsletter in my series of practical principles to help participants engage productively in discourse about controversial topics. The first, Who disagrees with Jo, articulated the foundational principle of depersonalising contributions. Then in, When the 'Shoulds' Don't Match , we focused on ways to define the nature of a sticking point in terms of the interplay of social values or 'shoulds'. Today the focus is on how we set participant's expectation of the structure of the discourse.

Principle #3: Establish Shared Expectation

"I don't know about you, but I love getting into issues. There's nothing like a good debate with friends where you discuss what's going on in the world. These deliberations can go on for hours. The dialogue knows no end. Even better is launching an inquiry into intergenerational issues at a family dinner. Who doesn't like quarrelling it out as the gravy boat goes round."

I MADE THE QUOTE UP , though we probably all know people just like that. Someone who leaves a trail of communicative carnage until they run out of willing participants and retreat to the internet. The tell tale sign is the moment, mid-conversation, when you realize you and they are engaged in completely different quests. I thought I was outlining my concerns about inequality, not signing up for a pop quiz on statistics. Or that we were deciding how to fix the car, not formulating a dissertation on what caused the breakdown.

By expectations, I'm not referring to the content or nature of the issue, but instead what we assume to be the purpose of the exchange. What are the ground rules? What counts as a good contribution? What's my role in this? There are many different types of discussion - indeed, a whole subsection of argumentation theory is dedicated to categorising them. To further complicate matters, we tend to use words like discussion, debate, and deliberation interchangeably when in fact they mean different things.1 It is no surprise then, that our expectations sometimes clash.

This is different from the content confusion we looked at in When the 'Shoulds' Don't Match - where people argue past each other because they're focused on different aspects of the same issue. This is about structural expectation. People can agree on what they're talking about but completely disagree on how they should be talking about it.

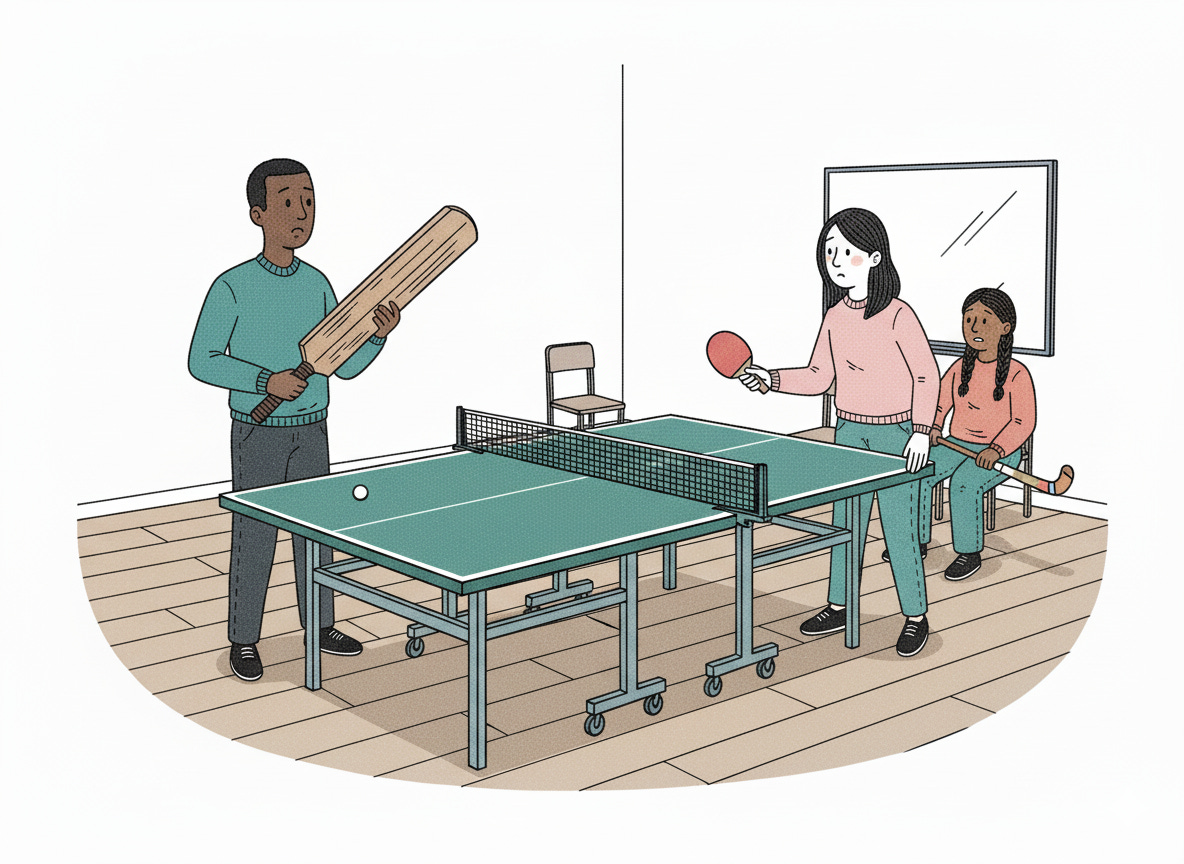

The ground zero example is the stereotypical family dinner quarrel where a, usually conservative, older relative clashes with a, usually liberal, younger member of the family.2 The elder treats it as a Debate - impressing the rest of the table by mustering the strongest possible arguments. The younger, perhaps having initiated the discourse, thought they were going into Dialogue, collaboratively sharing and negotiating understanding. Mistaking a Debate for Dialogue is the discussion equivalent of apples and oranges - clear markers of a category error.

Workshop Discussions

Happily, the remit of this newsletter does not cover family dinner arguments. But discussions play a significant part in any drama workshop - perhaps more than we might initially realise. We might find ourselves discussing the efficacy of particular performance conventions, the direction a devising process might take, or any number of choices in between. In parallel, we exchange thoughts about the social and political realities expressed in the work we produce or watch. We interrogate character decisions and the contexts that give rise to them. We look to the fictions we produce, imagining the world if they were to become real. Depending on the flavour of your work you may do some of these more than others, but you will unquestionably be leading discussions of one sort or another.

The trouble is, each of these requires a different approach. What works for weighing creative options can derail a conversation about social inclusion. The listening skills that build understanding might frustrate someone expecting rigorous analysis. Without clear signals about which type of discussion we're having, participants bring their own assumptions - and those assumptions might not align.

Think of it as three types you'll use regularly, two that require special care, and one to actively prevent.3 And as we've not had an etymological excursion for a while let’s dig under the origins of the words to see if they offer usable insights.

The Three (Core Workshop Discourse Types):

Critical Discussion:

- ‘discussion’ from the Latin discutere is based on a root cutere (to shake apart) shared with 'percussion and concussion'. Critical, on the other hand comes from Greek krinein (to discern or separate) the same root that gives us "crisis," the moment when things get cut one way or another.

Critical Discussion, therefore, involves both shaking and separating: shaking away the noise, discerning the consequential from the coincidental. It's about developing a shared picture by separating what holds up from what falls apart.

Expect to: Contribute to mapping a range of perspective on the issue. Personal opinions and insights can certainly inform this but are not the core focus. This is pre-persuasion work. We're not expecting minds to change, but we hope to use clarity to shake certainty - to create that useful confusion the Ancient Greeks called aporia where people recognise things might be more complex than they first thought.

Examples: Examining different perspectives on social and political themes, testing arguments , analysing competing interpretations of politically charged texts, evaluating the effectiveness of different theatrical techniques.

Inquiry

- from in quaerere, Latin for "to seek into" - looks backward. How did we get here? What's underneath this? This type of discussion only works if the participants recognise, indeed are motivated, by a knowledge gap. Something doesn't make sense? It's not clear why something happened or why someone acted in a certain way.

Expect to: Get into detective mode. Look for clues and evidence. Consider motivations and context. There may or may not be resolution - not everything can be explained.

Examples: The origins of social/political phenomena, investigating the origins of political tensions in a script, character backstory exploration, script analysis of how societal conditions shaped character choices.

Deliberation

- from libra, "the scales" - faces forward. What should we do? How do we weigh our options? Deliberation requires participants to move beyond understanding a problem to making choices about action. It's structured around weighing trade-offs: if we choose this path, what do we gain and what do we sacrifice?

Expect to: Weigh pros and cons of different choices. Consider consequences and trade-offs. Move from understanding a situation to deciding on action. The focus is on practical outcomes rather than theoretical analysis.

Examples: Deciding how to handle controversial content in devising, Forum Theatre interventions, weighing options for staging politically sensitive material, choosing which direction to take when developing work about current issues.

The Two (Situational - Use with Caution):

These can be valuable but require careful setup. Debate needs formal structure and agreed rules or it becomes combative. Dialogue needs psychological safety and genuine commitment to listening or it becomes performative.

Debate

- from battere, "to beat down". A structured process in which participants present and argue opposing viewpoints (which they may or may not actually support) aiming to persuade a third party that they have the strongest arguments.

Expect to: Present the strongest possible case for your position to convince observers. Listen strategically to identify weaknesses in opposing arguments. Focus on logical reasoning and evidence to persuade an audience rather than your direct opponent.

Examples: Used as a formal device for participants to explore two sides of an issue. An exercise in public speaking and developing argumentation. Dialectical approach to exploring the super-objective or fabel of a play.

Dialogue

- from dia + logos, "through words" or "through meaning" - is a process of negotiation, working through something together to reach understanding.

Expect to: Build mutual understanding through genuine listening and sharing. Suspend judgment temporarily to explore different perspectives. Focus on learning from each other rather than winning points. Be open to having your own views expanded or changed.

Examples: Exploring different lived experiences that inform perspectives on social issues, sharing personal connections to themes in the work, building empathy between participants with opposing political views, negotiating shared values when creating collaborative work.

The One (To Be Avoided):

And finally, not technically a discussion, but all too often mistaken as one:

Quarrel

- from querela, "complaint" - is about airing grievances rather than reasoning through anything. This is what happens when other forms of discourse collapse into expressions of frustration, blame, and hostility. It's the terminal stage where the goal shifts from understanding or deciding to attacking and defending.

Expect to: Find yourself defending yourself rather than your ideas. Notice conversations spiralling into past grievances unrelated to the original topic. Experience escalation where voices get raised and personal attacks replace reasoned argument. Feel like you're under siege rather than engaged in productive exchange.

Examples: I’m sure you already have some!

Establishing shared expectation

I can't imagine many contexts where we'd have the luxury to outline all of the above before launching into a discussion. And even if we did, would everyone sit still long enough? Probably not. Ultimately, it comes down to how we launch the discussion and continuously reinforce the expectation through our facilitation.

For Critical Discussion:

Set the scene visually, expressed in terms of definitions, connections, and contradictions

Launch:

"Let's map out what we're dealing with here - how do people define this differently?"

"We need to see the connections between these arguments and where they contradict"

"Let's build a visual picture of the different positions and how they relate"

"What are we actually talking about when we say [term]? Let's define our terms first"

Reinforcement:

"How does that connect to what we heard earlier about X?"

"I'm seeing a contradiction here - help me understand how these fit together"

"So we have two different definitions of X now - which one are we working with?"

For Inquiry:

Set the scene temporally, expressed in terms of context, evidence, causation, and correlation.

Launch:

"We need to trace the timeline - what led to what?"

"Let's look for evidence of what actually happened here"

"Why would the character do that?"

"How did we end up here?"

Reinforcement:

"Is that causation or correlation?"

"What's the evidence for that sequence?"

"Let's stay with what actually happened rather than what should have happened"

For Deliberation:

Set the scene conjecturally, expressed in terms of possibilities, advantages, and disadvantages

Launch:

"What possible ways might this play out?"

"Let's weigh the advantages and disadvantages of each option"

"What could happen if we choose path A versus path B?"

"We need to consider the full range of possibilities here"

Reinforcement:

"What might be the downsides of that choice?"

"Are there other possibilities we haven't considered?"

"That's a clear advantage - what would we be giving up?"

Switching Modes

Of course it's entirely possible, often necessary, to move between modes in the same session - but you have to signal the shift:

"Right, we've traced how we got here (inquiry). Now let's test these explanations and see which ones actually hold water (critical discussion). Then we'll figure out what to do next (deliberation).

Without those signals, people get lost. They're still operating under the previous set of expectations while you've moved on to the next.

Beware Pseudo-Discourse

But there's one expectation that's particularly tricky to manage through framing alone: the belief that any discussion means everyone gets to say everything they want to. It's certainly possible. Everyone gets their turn, but no one listens, and the group leaves unchanged. It feels democratic but it's actually the opposite of discourse. People speak past each other, air their views, and mistake participation for progress.

Now, I want to tread very carefully. There's a long, important, and powerful history of group work focused on silenced voices and marginalized perspectives. Claiming uninterrupted time to tell one's story is the cornerstone of emancipation. That's testimony. That's dialogue work. That's about recognition and understanding.4 But, that's not what we're talking about here.

There is a watered down, appropriated, fetishization of 'Your Voice Counts' that is anything but dialogue. It's a consumer-oriented paradigm where organisations treat participants like customers providing feedback. They dutifully perform "you said - we did" reports, conveniently skipping the middle part where they actually have to grapple with conflicting views. They "do" the things that cost nothing and ignore the rest. This borrows the language of testimony and dialogue but serves an entirely different purpose. And perhaps that's fine for a supermarket or a restaurant. The danger though is it instils individualistic expectations that claim legitimacy via the moral imperative of authentic testimony.

The result is insidious rather than dramatic. Jealousy when someone else makes the point you were about to offer, doggedly returning to a topic the conversation moved on from some time ago, fury that 'I still haven't got to my point' - this isn't about marginalization or silencing. It's about ego - the fear of not being seen to have said the clever thing. The consumer model of participation has created an expectation that everyone deserves a platform, confusing individual expression with collective discourse.

I used to run educational projects called "History Mysteries" - whodunits based on the curriculum. This was inquiry work: tracing backward to understand what happened. During interrogations, if one group of student detectives asked a question that another group had planned, the answer would be greeted with either a cheer or a groan. Not because someone had "stolen" their question, but because the answer either upheld or disproved the theory they were working on. The focus was on solving the case, not being the best detective.

That's what real engagement looks like. Participants invested in what emerges collectively, not in performing their individual cleverness.

Critical discussion isn't "everyone speaks until exhausted." It's about developing a shared picture. Some contributions build that picture. Others, while meaningful to the contributor, don't serve the collective inquiry. The facilitator's job is knowing the difference and having the courage to act on it.

Before It All Kicks Off

These first three principles create the groundwork for productive discourse about controversial topics. They follow a logical sequence that mirrors how conflicts typically develop - and how facilitators can prevent them.

Principle #1 De-personalise issues

Establish the object of discussion rather than making it about the person. "Who disagrees with Jo?" gets people focused on Jo's idea rather than Jo herself.

Principle #2 Define the nature of the issue

Define what kind of object it is. "When the shoulds don't match" identifies the competing values at stake in the issue and how they relate to one another.

Principle #3 Establish shared expectations

Set the rules for how to engage with it. "Did someone explain the rules?" frames the type of discourse needed before anyone starts speaking.

This progression moves from what we're discussing, to what type of thing it is, to how we should discuss it. Each principle builds on the previous one, creating the conditions where good thinking can happen.

But even with the best preparation, discussions can still veer toward conflict. The moment when someone drops an inflammatory comment, when emotions spike, when you can feel the room tighten - that's when you need a different set of tools.

The next set of principles will focus on those critical moments when, despite our best efforts, things seem to be sliding towards a quarrel.

I write the newsletter from various coffee shops, imagining I'm chatting with my subscribers over a cappuccino. So if you ever find an issue particularly helpful or thought-provoking, you can now literally buy me the coffee that will fuel the next one. This approach keeps the newsletter free and accessible for everyone while still allowing you to support the work when it resonates with you.

To cite this article:

Burns, B (2025) Did Someone Explain The Rules? The Philosophical Theatre Facilitator: www.philosophicaltheatrefacilitator.substack.com

© Brendon Burns 2025

Sources:

van Eemeren, F.H. and Grootendorst, R., 1992. Argumentation, communication, and fallacies: a pragma-dialectical perspective. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Walton, D.N., 1998. The New Dialectic: Conversational Contexts of Argument. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

For the sake of clarity I'm going to use 'discussion' or 'discourse' as the catch-all and "Discussion", "Debate", and "Deliberation" to refer to the specific technical terms.

Other combinations are available!

For the more academically minded I’ve distilled these from Donald Walton’s (1998) argumentation dialogues, substituting, Walton’s ‘Persuasion’ for the version of ‘Critical Discussion’ outlined in the pragma-dialectical theory of argumentation, developed by Frans H. van Eemeren and Rob Grootendorst (1992)

It might also be the subtle work we do to create conditions where unconfident participants can find the courage to take their space in a discussion.