The Art of What before When.

A perspective on getting stuck!

THERE IS AN OFT OVERLOOKED section in the middle of one of my all time favourite books 'Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance' by Robert Pirsig. The narrator, loosely based on the author himself, is on a road trip with his son Chris. Over lunch, one day, Chris decides to write a letter home to his mother. He stares at the blank paper for some time, then asks what the date is. He writes the date followed by “Dear Mom,” and then stares at the page again. In the end he turns to his father - “What should I say?”

I tell him getting stuck is the commonest trouble of all. Usually, I say, your mind gets stuck when you’re trying to do too many things at once. What you have to do is try not to force words to come. That just gets you more stuck. What you have to do now is separate out the things and do them one at a time.

You’re trying to think of what to say and what to say first at the same time and that’s too hard. So separate them out. Just make a list of all the things you want to say in any old order. Then later we’ll figure out the right order.

Not knowing where to begin must be one of the most common excuses for procrastination. Whether it be writing, workshop planning or devising, obsessing over the first word, exercise, or scene is a tempting way to avoid commitment.

Early on in my directing career I would spend the first couple of days desperately dodging the first scene. Of course, it's not unusual to begin with some introductory exercises and discussions and the time wasn't necessarily wasted. All said though, I was definitely getting hung up on how to start. Some years later I came across an anecdote in an interview with a director (I can't remember who) confessing to exactly the same “first line avoidance” habit . By then, however, my practice had evolved somewhat, and I was now consciously beginning rehearsals with work on a set piece or an ensemble part of the play. This might be the first scene, but it didn't necessarily have to be. The key criteria was that the section involved the whole cast in some kind of physical or rhythmic work. Ideally it would include some form of aesthetic problem solving - 'how might we show six hours of hole digging in five minutes', or 'how best to represent the way this dystopian society see themselves'.

My rationale was that this was a good way to maximise the time available for developing and rehearsing the routine. However, once I read that anecdote, I realised what I had been doing. In order to avoid the pressure of 'the first line' I was choosing to begin with something that was open and collaborative. I would come with a number of practical ideas for the scene - generally developed as part of the design process - but would keep them in my back pocket to allow space for the cast and I to discover how we were going to work together. Sometimes I'd need to draw on my pre-planned ideas, sometimes we discovered a completely different approach. Most often it was a mix of the two, where one of my initial ideas became a platform for something original to spring from.

I’m not trying to re-hash the much repeated maxim that no amount of directorial planning survives an authentic encounter with the cast - Peter Brook makes the point in The Empty Space, far more eloquently, and with significantly more weight, than I can. No, my intention in bringing up this story is the degree to which it underlines Pirsig's entreaty to avoid treating material and sequence as one and the same. My practice, as described above, allowed me to choose a scene best suited to creating/negotiating a working dynamic with a new cast rather than trying to squeeze those opportunities from the 'first' scene.

Spheres of application and domain independent learning

Pirsig's advice to his son might be directed to a specific activity, how to write a letter, but the same could easily be applied to business correspondence or academic writing. Taking inspiration from one sphere of the life and applying it elsewhere is known as 'domain independence' and is an extremely useful tool in developing practical wisdom. Whereas domain 'dependence' separates all learning into discreet boxes - 'independence' multiplies the positive impact of an insight by looking for applications across all the bits of life one is involved in. "What before When!" is clearly useful for writing, and I've outlined above how it might be applied in a specific directing challenge, but where else might it be applied?

Facilitation or Leadership Sphere

To apply "What before When" to workshop planning, you could consider separating content and sequence. Rather than starting with the first exercise, make a list of the exercises or activities that would fulfil the main purpose of the workshop. It's important that this is a list - even if the first idea is a strong one. Having several to choose from helps avoid automatically going with the initial idea for no other reason than it happened to be the first one that came to mind. Then, having selected one or two exercises to act as the core of the session, thought can then be turned to sequence. Adding a warm-up and introductory exercises is much easier when you know where you are trying to get to. Furthermore, you will have already identified a range of suitable replacement exercises if for some reason you need to change the plan on the day.

Participant Skills Sphere

The episode in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance above is in fact an introduction to a section on 'Stuckness.' I am sure anyone who has ever led a devising process, particularly one involving participants working in groups, is familiar with the cry of 'We're stuck'. Group decision-making rapidly flounders when considering "what to do next”. Instant relief can be given by separating 'what we are going to do next' from 'what we could do next'. If you add in the discipline of placing possible ideas on individual pieces of paper/post its/whiteboard tiles, you also create a degree of separation between the idea and the person who came up with it. Prioritising and selection then becomes a non-linear physical process rather than a hierarchical one. Another idea to break a devising impasse, similar to the directing practice I related above, is to jump to a section that you already have a strong idea for rather than wallowing in the pain of inspiration constipation!1

Script/Character Analysis Sphere

Applying 'What before When' to analysing a character involves a process of reverse engineering. The 'What' is already articulated in the text itself. But hidden behind the scripted actions are a number of other things the character could have said or done to accomplish their goals.

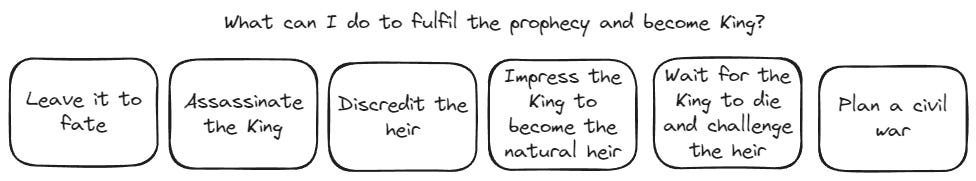

Considering the 'roads not taken' is useful in two distinct ways. Firstly, it challenges determinism - the notion that the events on stage are the inevitable consequence of previous actions. In this way, the exercise aligns with the Brechtian technique of “Fixing the not…but…"2 . Secondly it provides an opportunity to move beyond the dualism of Brecht’s not/but to a complex hypothecation of both the range of options open to the character and the criteria used to decide what to do first. If we were to consider, for instance, Macbeth's decision to kill King Duncan when he visits Inverness, a simple not/but analysis shows the protagonist choosing:

NOT to leave it to fate (Chance may crown me without my stir)

BUT to assassinate the King (I go and it is done)

Both these perspectives are well served by the text - clearly articulated in the lead up to the murder. However, if we instead imagine Macbeth writing a 'What Before When' list, we might end up with something a bit like this:

What character insights do we get from the fact that Macbeth chose the assassination over the other options?

Well, as stated by the thane himself, and his wife, he is very ambitious and a man of action. Leaving it to fate is not an option.

Challenging Malcolm or starting a civil war would mean explicitly and publicly revealing his desire to be King. Impressing Duncan and discrediting Malcolm/Donalbain would only work in combination and, again, would likely involve being seen to be manoeuvring to take the throne. The assassination is the only way Macbeth gets the crown while still looking like he didn't want it.3 Perhaps this points towards, not just ambition, but a somewhat narcissistic tendency in Macbeth. If so, it would explain both his sense of superiority and his desire for approval. His willingness to dispose of Banquo and later sensitivity to criticism equally fit the profile of a narcissist.

Lady Macbeth's describes her husband as "too full o' th' milk of human kindness" and this is often taken as a genuine observation of his character. However, isn't that exactly what a narcissist would want his wife to believe? The fact that she also states that he “would'st not play false and yet would wrongly win” is perhaps more perceptive. She recognises that Macbeth would be happy to accept an immoral outcome as long as he is not seen with blood on his hands. There's more going on here than just ambition.

In short…

In this post I’ve tried to provide some examples of how a domain specific technique, in this case a solution to writer's block from a seventies cult novel, might be used across different spheres of activity. Simply put, cultivating domain independence gives 'bigger bang for your buck'! Time invested in getting to the root of a problem in one area offers a bigger return if you can apply the insight elsewhere. It is also the secret to coming up with stuff other people haven't thought of.

Afternote:

I’m experimenting with the format this month. Rather than sending a digest of several articles I’m planning on releasing one every couple of weeks. It would be good to get some feedback on this - so if you have a preference let me know below.

Also, to make the newsletter as useful as possible, once a month I’d like to to respond to specific questions, concerns, or issues emerging from your facilitation work. I’ll make an official announcement in the next couple of days but in the meantime if you’d like your question to feature this month send me a message via the button below.

References:

Brecht, B., Silberman, M. and Giles, S., 2015. Brecht on theatre. Third edition ed. Drama and performance studies. Translated by J. Davis, R. Fursland, V. Hill, K. Imbrigotta and J. Willett London New Dehli New York Sydney: Bloomsbury.

Pirsig, R.M., 1974. Zen and the art of motorcycle maintenance. London: Vintage

This is very similar to the facilitation fallacy of 'Naming the band' which uses the metaphor of a group spending hours thinking of name for the band before they've even practised a song. It refers to a dynamic in which a relatively minor choice is used as an excuse to delay/defer substantive work.

"they will act in such a way that the alternative emerges as clearly as possible, that their acting allows the other possibilities to be inferred and only represents one out of the possible variants. An actor will say, for instance, ‘You’ll pay for that’, and does not say ‘I forgive you’... In this way every sentence and every gesture signifies a decision; the character remains under observation and is tested. The technical term for this procedure is: fixing the not – but." - From: A Short Description of a New Technique of Acting That Produces a Verfremdung Effect in Brecht on Theatre

Of course, a lot hinges on Malcolm and Donalbain running away and being blamed for the murder. That said, it could be argued that they were also on the hitlist but were saved by the knocking at the gate.