The Philosophical Theatre Facilitator Digest June 2024

Welcome to the June 2024 monthly digest.

Contents

1. How do you fly your kite?

Sometimes I hold on too tight but surely that’s better than losing control?

Finding the appropriate balance between order and creativity is probably one of the most significant ongoing challenges for any facilitator. Whether you conceive of the distinction as that between control and freedom, discipline and play, or focused and fun, it remains a unique balancing act to be replayed every time we run a session. Without doubt, most facilitators have a tendency to lean one way or the other. Some, adhering to old-school performing arts training paradigms, insist discipline is the route to freedom. Others, drawing on critical pedagogy and other developmental theories, abjure top-down control in favour of free agency. Like most things, tyranny exists at the extremes of both positions. The laid back invitation to 'do whatever you feel' is as suffocating as the dictatorial 'do what I say'. Happily, very few occupy these extreme positions. That said there is also no definable middle ground and as a result we face a 'balancing act' on a daily basis. Much as we would hope that instinct will guide us, it can be useful to take a moment to conceptualise the dynamics at play.

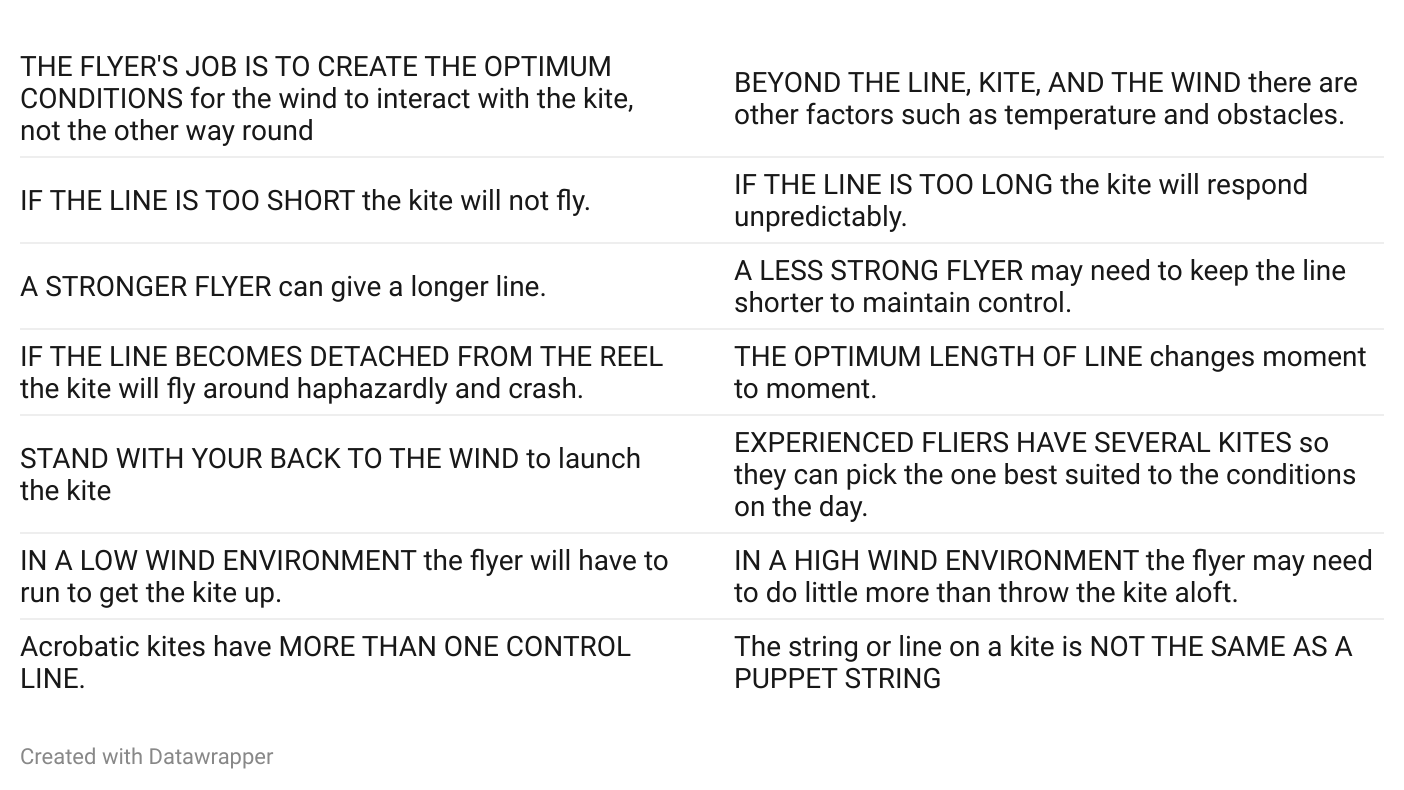

A metaphor I like to use is that of flying a kite. As everyone knows, kites fly due to the interaction between the wind and the surface area of the kite fabric. If there is insufficient wind the kite will crash (usually) tail first. Too much wind and it will nose dive or fall apart. The only control the flyer has, beyond the location and timing of the launch, is the length and tension of the line. So, to put the concept to work let's imagine the 'kite' symbolises the activity or exercise, the 'wind' the energy and engagement of the participants1 and the kite flyer the facilitator. If this is the case what insights can you glean from the following:

Now, I know what the metaphors means to me - standing with your back to the wind, for instance, makes me think about focusing on where participants want to go, not just where they've been. But the true utility in practice metaphors is found in a personal reflective response. IF the challenge of balancing of order and creativity can be seen in the relationship between the wind, the kite and the flyer, which of the statements above ring true for you (positively or negatively).

How do you fly your kite?

2. The issue with issues!

The Issue Song:

Religion, acne, bullying, cancer

Issues, issues

Abortion, suicide, knife crime, dogma,

Issues, issues

Female genital mutilation

Issues, issues

There's so many issues in the world today

We need to see them in a play.

And he can write them, hip-hooray

Because he's the king of the issues.

I'm the King of the issues,

Issues, issues, issues

The League of Gentlemen Live Again, Hammersmith Apollo, 2018

LET’S FACE IT, there is an issue with 'issue work' in drama and theatre! As hilarious as the the League of Gentlemen's TIE parody is, I dare anyone involved in educational theatre to watch 'Legz Akimbo' in action without experiencing a pained wince of recognition. This is perhaps unsurprising. Messrs Gatiss, Pemberton and Shearsmith have stated that they drew inspiration from theatre companies they worked with early in their career.

Of course, the appalling insensitivity, tokenism and blatant prejudice to be found in 'Everybody's Out', 'No Home 4 Johnny' and 'Scumbelina' is exaggerated for comedic effect. I am certainly not suggesting, for a moment, that these aspects are reflected in the work of established theatre education professionals. Nothing could be further from the truth2.

But, there are few practitioners who do not secretly flinch at the mention of 'issue based plays' or 'issue led workshops'. Visions of stereotypical devised work or the bludgeoning message of drugs/homelessness/bullying TIE performances are hard to escape. And yet, I'm guessing, we've also all experienced, and possibly created, powerful, thought-provoking work in this field. The difference, I would argue, is in how we unconsciously interpret the word 'issue.'

Issue or Problem?

In common usage, 'issue' has become synonymous with 'problem'. We might talk about psychological issues or IT issues as easily as we might refer to psychological or IT problems . But then we also have usage in other contexts - “this month's issue of Vogue” or “the issue of marital union” (children) - where 'problem' definitely doesn't work as a synonym. However, if we take a look at the etymology of the term 'issues', we can see a root that makes sense of all cases.

We derive the modern word issue from Middle English ischewe meaning 'out flowing', which in turn comes from Old French issir (to exit) and a root in Latin exire (to go out). So, stripped back to its essential meaning, an 'issue' can be seen as something that flows out of, or is produced by, something.

To contrast this, 'problem' comes from the Ancient Greek πρόβλημα (próblēma), meaning barrier, obstacle, or fence, itself rooted in προβάλλω (probállō) - to throw something in front of someone. So, while a 'problem' is static - an obstacle to be overcome, an 'issue' is dynamic - in motion. Hegel defines the cause of this motion thus:

“contradiction is the root of all movement and life; it is only in so far as something has a contradiction within it that it moves...”

Hegel (2010:382)

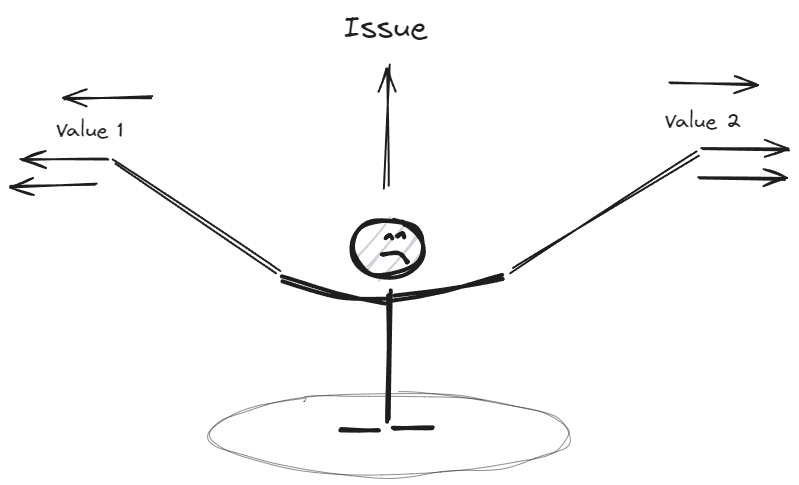

'Issues', then, could be seen as emerging from, or flowing out of, contradictions. Social/political/personal contradictions create social/political/personal issues. It can be helpful to conceptualise this visually:

Our character (an individual or society) is being pulled in opposing directions in their attempt to adhere to contradictory values or desires. The 'tug of war' style tension creates movement in a third direction - and what emerges is 'the issue.'

So, to take recreational drug addiction as an example, the issue is produced by the contradiction between the desire to feel good/escape bad feelings and the desire for physical/mental wellbeing and avoidance of harm. Resolving the contradiction becomes more complex if the two values are closely weighted (even more so if we take into account other value pairings that sit in parallel with this issue). There is no clearly defined answer, only renegotiation of the relative weight of the values to find an acceptable compromise. There is no win-win scenario with an issue.

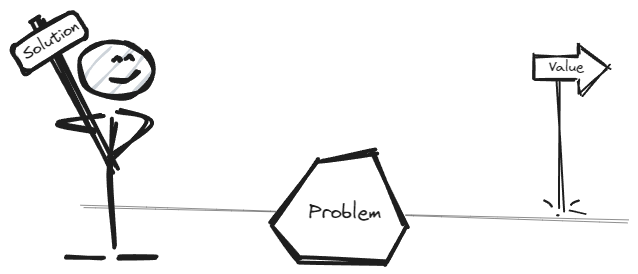

Finding a solution when framing addiction as a problem, however, is much easier. If 'drug addiction' is seen as an obstacle, then theatre work that hammers home moral messages suddenly make sense. There will be no problem if you 'just say no', or are sufficiently scared by the melodramatic demise of the protagonist to stay away from 'drugs'.

This then, I would argue, is the key difference between the cringe inducing 'issue plays' discussed in the introduction and the more impactful work we might have seen, or hope to produce. The former provides pre-prepared answers, the latter, creates space for questions and analysis. One is an attempt to impart dominant values, the other an invitation to weigh a range of values against each other. It may be an oversimplification, but the difference between training and education also comes to mind.

Practical Applications.

You might have noticed that the tug of war illustration of 'issue' above bears some resemblance to the final scene of Brecht's Caucasian Chalk Circle - this is no coincidence. The notion of human action being rooted in a nexus of contradictory forces is absolutely central to Brecht and Piscator's vision of Epic Theatre. I'm sure many of you have already recognised that what I've been articulating about issues vs problems is essentially the differences between dialectical vs didactic forms of theatre and theatre making. With this in mind, there are a plethora of existing schemes and exercises that can be used to ensure your 'issue' work sits in a dialectical rather than didactic/solution frame.

Using contradictory stimulus to begin writing or devising, for instance, will allow issues to emerge authentically. The challenge of resolving conflicting desires/values/imperatives can be a strong starting point for an improvisation. Equally, an existing issue can be reversed engineered to discover its component contradictions. This is particularly useful in scene or character analysis and can be very effective in avoiding polarising value judgements when a character does something we might not agree with.

There are two things I feel I need to make very clear as I wrap up this section. Firstly, I have focused on recreational drug addiction due to its ubiquity as an example of 'bad' TIE and, for clarity and brevity, the issue analysis of addiction is purposely simplistic. Real issues are multi-layered, the contradictions messy and difficult to measure or quantify. It takes considerable skill and care to negotiate the issue of issue work!

Secondly, and most importantly, this is not an exercise in semantics. I can think of many current uses of the word problem that fully encompass the characteristics of an issue (Freire's 'Problematisation/Problem Posing Education' and Conklin's 'Tame vs Wicked Problems' both come to mind). Language is constantly changing and evolving. What a word meant and what it means now are completely separate things. The etymology is useful only in so much as it helps us distinguish between concepts that have become conflated over time. This is not about being the 'word police'. You could argue that the words don't matter as long as the thinking is precise. I agree. It is, however, much harder to communicate precise thinking with imprecise vocabulary.

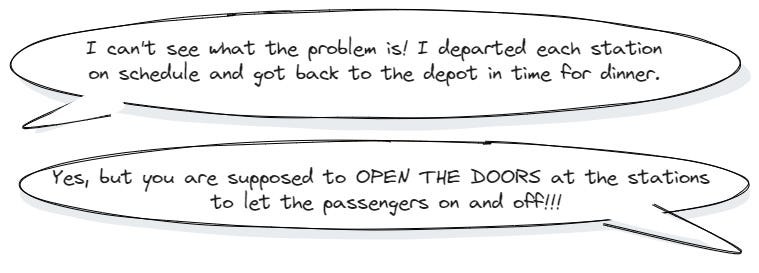

3. The Train Driver’s Dinner

IMAGINE A FACILITATOR who speeds through a workshop like a train driver, determined to reach the final stop on time, no matter what. I mentioned this error briefly in my first post on facilitator fallacies, and facilitators succumb to it more often than we would like to admit. Maybe the workshop started late, but you still want to cover everything. Perhaps you stick to a rigid schedule, even if participants are struggling to understand. Or you find yourself resorting to only demonstrating complex technique without giving enough time for practical engagement.

Understanding the error:

It would be easy to dismiss this as simply an instance of 'the planning fallacy', the tendency to optimistically schedule timings based on a perfect scenario. But our focus here is less on why time is short and more on what the facilitator decides to do about it.

As is typically the case with facilitator's fallacies, what we are questioning are specific choices made 'in the moment' that, upon reflection, seem illogical.

Why on earth would we feel compelled to rush through, 'covering' everything in the plan even though it means that nothing is covered properly?

In hindsight, The Train Driver's Dinner approach is clearly misguided. Trying to cram everything in sacrifices depth for breadth, leaving participants overwhelmed and key insights underexplored. So, why do we fall into this trap?

The root of this fallacy lies in our desire to provide value. We want the workshop to 'go well'. However, of the numerous conditions that contribute to a successful workshop, none are definitive in isolation. For example, ensuring participants' physical safety is fundamental, but simply avoiding accidents doesn't guarantee success.

Prioritising adherence to planned timings is attractive. It provides a clear, straightforward measure of 'how it is going'. It's pretty simple: the session is on schedule, or it isn't. As sensible as that sounds, we are confusing the benefits of our 'planning'- where we refine aims and considering various ways of achieving them, with 'the plan'- the last version of our thinking before we dive into the workshop.

The 'plan' is not the only outcome of 'planning'

Most of the time, we know that 'the plan' is provisional. We mentally cross-reference between plan, planning and the reality on the ground, updating sequence and timings to best deliver the aims. But occasionally, especially when we’re under a lot of pressure, the plan can become an anchor. It can lock us in, making it tough to think beyond the assumptions we made before the workshop. When this happens, the plan is no longer a means of achieving the aims, it becomes the aim itself.

Strangely enough, in all the sessions I have observed, the most common cause of a 'Train Driver's Dinner' is not a lack of time, but a plan that is not working. Faced with a lack of engagement or seeing activities fail to meet intended aims, the facilitator gives up and resorts to the written plan. They put their head down (literally not seeing the participants) and process the group through the pre-prepared sequence, often speeding up and getting louder to cover the absence of participation.

Potential consequences:

Questions and discoveries are ignored.

Anyone impeding the schedule/plan becomes an 'obstacle'.

Pseudo-achievement. Participants will not remember what happened in the session.

Ways of interrupting the fallacy:

Plan from core intention. Make sure you have identified aims before choosing activities.

Include elements of divergent thinking in your planning. Don't just go with the first idea and follow it linearly, consider a variety of ways of meeting the aims.

Establish options for simplifying or extending activities.

Ensure the written plan specifies the aim of each exercise. Then, when you need to adapt something, you'll be reminded what the original intention was.

Develop a practice of identifying and monitoring a range of qualitative metrics that can act like a Station Master's whistle - signalling the participants are 'on board'.

In hindsight, consider where more natural moments of completion might have occurred.

Always an error?:

Sessions generally have a fixed start and end time, with little or no flexibility to run over. This is a practical limit. Even when running over is possible, to do so without tacit agreement from the participants is to sublimate their time to your 'plan.' But, whilst good timing is necessary for a successful workshop, it is not, in and of itself, a sufficient condition.

Finishing on time is a professional requirement and can only rarely be overlooked. However, finishing the workshop within the time available is equally important in the sense of having reached a point of completion or pause (even if that end point is different to the one in the plan).

I think it's important for the thought experiment to note that the wind represents the energy and engagement in the room, not the participants themselves. Furthermore, energy and engagement can ebb and flow just as air currents are variable and can change depending on altitude.

Hastily thrown together TIE programmes by actors with no educational experience out for a quick buck are, unfortunately, another matter altogether.

Hi Brendon.

Kite-flying – it’s spot on for what I do with poetry and spoken word. It’s all about catching that perfect gust of inspiration and letting it lift the words right out of us. But hey, you can’t just let the kite fly wild, right? There’s a beat, a rhythm to keep in check.

When I’m leading a workshop or taking part in a slam event, it’s like I’m holding onto that kite string, feeling the pull of ideas from the people I’m with. We let our imaginations jump on the wind, but I’m there to keep us from flying off into the chaos. It’s this dance between letting loose and keeping it tight – that’s where the magic can happen.

Your metaphor? Never thought of it this way before but it makes real sense. Standing with my back to the wind makes me think about pushing forward, not just rehashing the old stuff. It’s about where we’re headed with our words and stories.

So, how do I fly my kite? I keep my ears open to the whispers of creativity and my hands steady on the pulse of the piece. It’s all about riding that breeze of freedom while maintaining overall control.

Ian