The Power of Moments

Book Review

One of the initial ambitions of this newsletter was to create a space for sharing and dissecting impactful books and resources – those gems that might not show up on the radar. The type of content that doesn’t usually find its way onto a theatre practitioner’s to-read list but holds the potential to change the way we think about our work.1

This is the initial instalment in what will become a regular feature – part guidebook and part book report. The concept is straightforward enough: extract the ideas and methods that can be easily applied, the ones you can use rather than simply look at from afar. Consider it the abridged equivalent gives you enough to put ideas into practice while hopefully also convincing you the entire book is worth the investment.

Flat workshops, underwhelm and other crimes:

NO ONE WOULD PURPOSELY lead workshops, classes, or rehearsals that are as flat, all on one note, lacking climax or clear moments of decision. An unremarkable or unmemorable workshop is unlikely to have been impactful.

Of course theatre facilitators, stage directors and drama teachers know about ‘moments’ - it’s the essence of dramatic action. I can only imagine how many of you will be inwardly quoting Aristotle on inciting incident, rising action and climax or wondering about Brecht’s nodal points as you read the rest of this post. We will call out a scene with no key moments as ‘flat’ or ‘all on one note.’ We will live with a slightly ropey bit of ensemble work knowing it will be overshadowed by the big dance number that follows. But, do we give the same consideration to the potential of moments across a series of workshops, rehearsals, or classes? And does it matter?

Pragmatic non-fiction books rarely reveal something completely and utterly new - something the reader has never encountered. What is more likely is that the text names and explores a concept or phenomenon that we are already intuitively aware of but would struggle to articulate if asked. And this certainly applies to Chip and Dan Heath’s 2017 book on why certain moments have extraordinary impact.

The Power of Moments

We all have defining moments in our lives meaningful experiences that stand out in our memory. Many of them owe a great deal to chance: A lucky encounter with someone who becomes the love of your life. A new teacher who spots a talent you didn’t know you had. A sudden loss that upends the certainties of your life. A realization that you don’t want to spend one more day in your job. These moments seem to be the product of fate or luck or maybe a higher power’s interventions. We can’t control them. But is that true?

Must our defining moments just happen to us?

The Quick Read:

A defining moment is a short experience that is both memorable and meaningful.

Some moments matter more than others: Across a sequence of activity beginnings, peaks, and endings seem to have the most impact.

Elevate peaks, fill pits, and ignore potholes: A strong, positive moment (peak) and ending outweighs numerous minor dips (potholes). However, a single negative peak or ending (pit) can easily overshadow everything.

Memorable moments accelerate development: It’s tempting to dismiss ‘moments’ as icing on the cake - ‘workshop jazz hands’. However research points to the developmental importance of moments strengthening group relationships, increasing motivation and marking milestones/transitions.

Meaningful moments don’t just happen; they are crafted. There are four key elements to consider when designing impactful moments:

Elevation: Elevate moments above the ordinary

Insight: Create moments of realization and understanding.

Pride: Moments of achievement and recognition fuel a sense of accomplishment.

Connection: Shared experiences and emotional bonds catalyse meaning and forge lasting memories.

Don’t take ‘moments’ for granted. Packed schedules, focus on grand or long term goals, replicating previous peaks, lead us to forget to create opportunities for meaningful moments to emerge.

Defining moments:

The driving thrust of the book is a simple observation - some moments in our lives are much more meaningful than others. OK, no great revelation there. Anyone asked to relate their life story will focus on a selection of defining moments. The question Chip and Dan Heath bring to the book is whether such moments have to be left to chance or whether they might be authored, planned or created.

From here the book could have gone one of two ways. It might have pursued a self-help path, providing a recipe for individuals to create their own ‘defining moment’.2 Instead, and more usefully for us, the authors explore how teachers, leaders, employers, businesses etc. might create the conditions for such moments to occur.

Why some moments matter more than others:

What’s indisputable is that when we assess our experiences, we don’t average our minute-by-minute sensations. Rather, we tend to remember flagship moments: the peaks, the pits, and the transitions.

The Heath brothers draw on research into a phenomenon called ‘Duration Neglect’: the observation that people tend to ignore most of what happens and instead rate experiences on the basis of just a few specific moments. The counterpart to ‘Duration Neglect’ is known as the ‘Peak End Rule’3 - that the moments we usually remember are 1. the best or worst bits and 2. the beginning or end of an activity - the rest fades from memory.

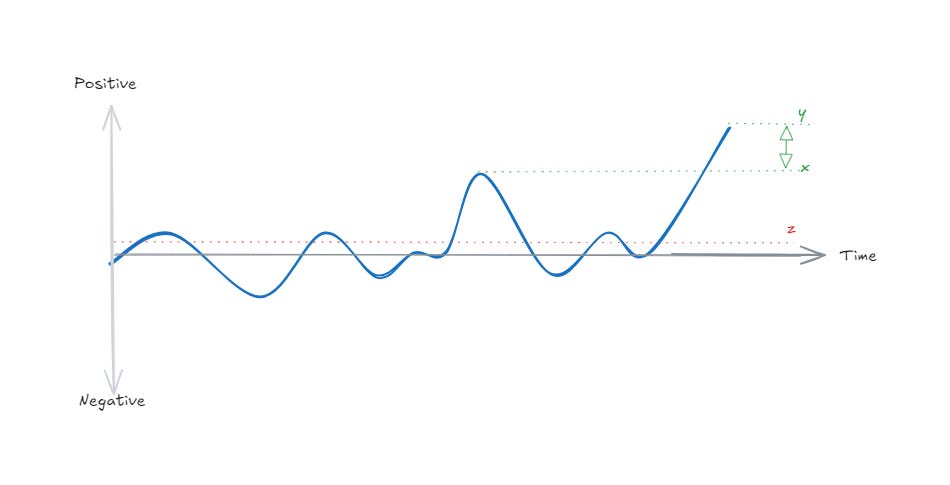

To think about this visually, consider the diagram below showing participant perceptions of a workshop over time. We have moments of positive experience (peaks), moments of negative experience (pits and potholes) and bits which are neither positive nor negative (meh!)

Peak End rule suggests participants will perceive the quality, meaningfulness, or impact of the activity as falling somewhere in between the peak (x) and end (y) moments rather than charting an average from all the pits and peaks (z).

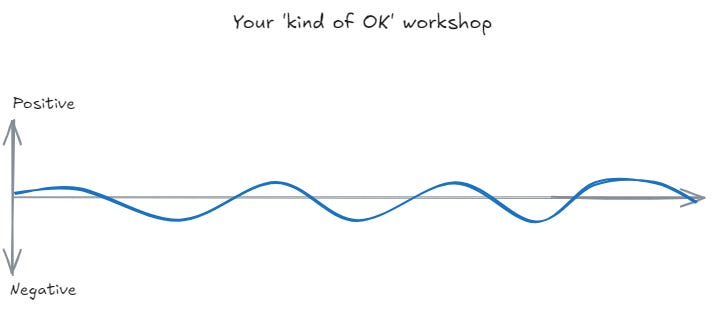

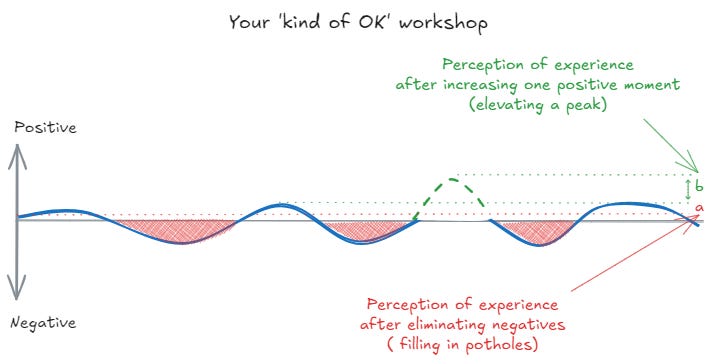

Once again this might seem fairly obvious. However, let’s imagine you have a stock session you run on a fairly regular basis. It’s not your best workshop, it tends to fluctuate between mildly positive and mildly negative moments. It’s OK, but not great, and you’d like to improve it.

The temptation for many, I think would be to look for ways to address the sections that fall below the line. In this example these are not ‘pits’ - significantly negative moments that must be addressed, but ‘potholes’, sections that don’t quite hit home or muster a lot of enthusiasm. If the duration neglect / peak end rule is correct, though, filling in the potholes would only raise the perception of the activity to just above ‘meh’ (a). Putting similar effort into elevating one of the peaks, on the other hand, would significantly improve impact/memorability (b).

The advice then, is to fill pits, ignore potholes and elevate one or more peaks.

Jazz Hands for Workshops?:

That effort spent completely eliminating potholes (minor negative moments) makes very little difference, certainly rings true to me. Just as you eliminate one pothole, another will appear and an awful lot of participants won’t even notice you’ve filled them in. The potholes might also be mandatory - part of a curriculum or section of a script.

However, I can’t help but worry that what is being suggested is the equivalent to Juvenal’s famous quote about ‘Bread and Circuses’ - that the people can be appeased, come to ignore the negatives, as long as they have food and entertainment.4 Seen in this way the ‘peak’ is a distraction at best and bribery at worst - like throwing a pizza party for participants at the same time you are handing out evaluation forms! Some examples in the book, particularly those focused on consumer oriented ‘customer experience’ moments, underline this interpretation. Furthermore, the emphasis on ‘peaks’ seems to contradict approaches such as Deliberate Practice that recognise the need for sustained, focused, development.

Accelerators of development:

The “bread and circuses” concern is valid — I’d wager we’ve all witnessed those cringe-worthy moments engineered to paper over deeper issues. However, the examples in the book from educational and community engagement contexts point to an altogether more progressive application of the research.5 Defining moments, when crafted with care, rather than calculated superficiality, can serve as genuine catalysts for development.

Consider this: rather than merely offering a shiny distraction from the negatives (which, let’s be honest, rarely fools anyone for long), a well-timed defining moment might just reframe how participants see the whole process. Picture the group who suddenly grasps they can transcend the hum drum of daily life, or the participant who discovers their voice carries weight in discussion. These are no small achievements — they’re jolts of clarity that can crystallize months of practice into something coherent.

And this is where we can see the practical impact. That burst of insight, that flash of communitas? It doesn’t undermine the tedious slog of deliberate practice — it powers it. The difficult process of improvement suddenly doesn’t feel like punishment but possibility. The group are no longer working against the drag of inertia. These transitional moments become the tipping points that offer the exact energy to apply oneself more fully to the work.

From a distractive moment to a transformative one.

The book draws on a range of scientific research and case studies and finds positive defining moments draw on four key elements:

Elevation

Moments of elevation are experiences that rise above the routine. They make us feel engaged, joyful, amazed, motivated.

Some activities have built-in peaks, such as games or recitals or celebrations. But other areas of life can fall depressingly flat.

Elevated moments usually have 2 or 3 of these traits:

(1) Boost the sensory appeal;

(2) Raise the stakes;

(3) Break the scriptThe third part—break the script—requires special attention. To break the script is to defy people’s expectations of how an experience will unfold. It’s strategic surprise.

The most memorable periods of our lives are times when we break the script.

Moments of elevation can be hard to build. They are no one’s “job” and they are easy to delay or water down.

Insight

Moments of insight deliver realizations and transformations.

They need not be serendipitous. To deliver moments of insight for others, we can lead them to “trip over the truth,” which means sparking a realization that packs an emotional wallop.

Tripping over the truth involves:

(1) a clear insight,

(2) compressed in time and

(3) discovered by the audience itself.To produce moments of self-insight, we need to stretch: placing ourselves in new situations that expose us to the risk of failure.

Mentors can help us stretch further than we thought we could, and in the process they can spark defining moments.

The promise of stretching is not success, it’s learning.

Pride

Moments of pride commemorate people’s achievements.

There are three practical principles we can use to create more moments of pride:

(1) Recognise others;

(2) Multiply meaningful milestones;

(3) Practice courage.Effective recognition is personal, not programmatic. (“Star Performer of the Month” doesn’t cut it.)

To create moments of pride for ourselves, we should multiply meaningful milestones—reframing a long journey so that it features many “finish lines.”

Moments when we display courage make us proud. We never know when courage will be demanded, but we can practice ensuring we’re ready.

Courage is contagious; our moments of action can be a defining moment for others.

Connection

Moments of connection bond us with others. We feel warmth, unity, empathy, validation.

To spark moments of connection for groups, we must create shared meaning. That can be accomplished by three strategies:

(1) creating a synchronized moment;

(2) inviting shared struggle;

(3) connecting to meaning.

- Groups bond when they struggle together. People will welcome a struggle when it’s their choice to participate, when they’re given autonomy to work, and when the mission is meaningful.“Connecting to meaning” reconnects people with the purpose of their efforts. That’s motivating and encourages “above and beyond” work.

In individual relationships, we believe that relationships grow closer with time. But that’s not the whole story. Sometimes long relationships reach plateaus. And with the right moment, relationships can deepen quickly.

Defining moments can contain any combination of these elements but will generally contain at least one.6 From the perspective of a facilitator/director teacher these could be layered or spread across a session, a workshop/rehearsal process or an academic year.7 A timeline may naturally offer a specific moment - post show euphoria as a moment of pride and connection springs to mind. But customary timelines need not be definitive. An early moment of elevation or insight may give the momentum, motivation, or trust required to get to the ultimate aim of the workshop. Likewise, a moment of pride or connection just before production might help the cast smuggle the best of the rehearsal room through to the first night.

Summary

What strikes me most about this book is how it validates something theatre practitioners have always known but rarely apply beyond performance — that structure and spontaneity aren’t opposites but dance partners. Just as we wouldn’t dream of staging something without considering its dramatic arc, perhaps we shouldn’t run workshops without thinking about the distribution and creation of defining moments.

The Heath brothers offer us a roadmap: create moments that elevate above the routine, spark genuine insight, celebrate achievement, and forge connection. And yes, there’s something slightly unsettling about the calculated nature of it all (are we engineering authenticity?), but perhaps that discomfort is worth wrestling with if it means fewer flat workshops and more genuine breakthroughs. The mathematics are surprisingly simple: one strong peak can outweigh a dozen minor irritations, while a single pit can poison everything that came before. The irony, of course, is that by planning for spontaneity — by designing space for elevation and discovery — we might just create the conditions where genuine development becomes more likely to occur.

Questions for Reflection

What kind of moments do you naturally create?

What type of moments are missing from your practice?

Thinking of a span of multiple sessions - are key moments spread out or clustered together?

When are the key moments of connection in a rehearsal process?

Does this differ depending on whether the performers are professional or not?

Other books I’m currently reading:

The Missing Thread by Daisy Dunn

Dunn, D., 2024. The missing thread: a women’s history of the ancient world. New York: Viking. The Missing Thread - The Guardian Bookshop

There Is Nothing for You Here by Fiona Hill

Hill, F., 2021. There is nothing for you here: finding opportunity in the twenty-first century. Boston, Mass: Mariner Books. There Is Nothing for You Here - The Guardian Bookshop

Reality is not what it seems: the journey to quantum gravity by Carlo Rovelli

Rovelli, C., 2017. Reality is not what it seems: the journey to quantum gravity. Translated by S. Carnell and E. Segre UK: Penguin Books. Reality Is Not What It Seems - The Guardian Bookshop

Get the The Power of Moments:

Heath, C., 2017. The Power of Moments: Why Certain Experiences Have Extraordinary Impact. New York: Simon & Schuster.

The Power of Moments - The Guardian Bookshop

To cite this article:

Burns, B (2025) The Power of Moments. The Philosophical Theatre Facilitator: www.philosophicaltheatrefacilitator.substack.com

© Brendon Burns 2025

I have a confession to make: I don’t read many drama books. I used to read them all, but at some point over the last few years I fell out of the habit. It’s not that I’m any less interested, nor do I believe there’s nothing left to learn.

One reason is that most drama books today fall into two distinct categories. On one hand there are collections of games/exercises and on the other, more academic, analytical texts. The former tend to be written by generalist practitioners and the latter invariably (though not exclusively) the product of applied theatre research. Of course there’s nothing inherently wrong with these books - I’ll no doubt be mentioning some in future posts - but, I do miss the books that used to sit in a third category: those written by seasoned practitioners, sharing hard-earned insights and hypotheses born from a desire to understand, improve and communicate practice.

The other reason, as you’ll probably have noticed from past posts, is that I try to draw on a wide range of sources, looking for useful crossovers from science, philosophy, history, and politics. Staying within any echo chamber, drama/theatre included, leads to domain dependence and diminishing returns. So whilst I will review drama/theatre books from time to time, I’m going to focus on texts that subscribers might be less likely to come across .

If this had been the case, I would have stopped reading. Being open to the ‘moment’, I can go with; recognising the significance of a ‘moment’, that’s important; but self-consciously creating your own ‘defining’ moment? Surely that would be the height of solipsism. Admittedly, the book does contain examples of individuals designing events/ceremonies/rituals to mark their own life transitions, but these are almost always at the suggestion of others and follows recognition that they are already ‘in’ a defining moment

In reality ‘End’ refers to any transitionary moment, but I’m guessing someone thought ‘Peak End’ is catchier than ‘Peak Transition Rule’!

Juvenal was an ancient Roman satirical poet. The phrase bread and circuses in Latin panem et circenses is the inspiration for the city of ‘Panem’ in The Hunger Games.

I don't have the space here to summarise the case studies - nor do I want to take away from your pleasure in discovering them in the book - but the ones I am thinking of are: The Trial of Human Nature, YES Prep's Senior Signing Day and the Community-Led Total Sanitation project in Bangladesh

In this instance specifically ‘positive’ defining moments. The authors acknowledge: “there are categories of negative defining moments, too, such as moments of pique: experiences of embarrassment or embitterment that cause people to vow, I’ll show them! … but we will not explore this category in detail, for the simple reason that our focus is on creating more positive moments.”

When working in HE I always tried to timetable with a director’s mindset - considering the journey through the week, term and year. Just as key plot points need to laid out to build to climax so learning outcomes across modules should build. Filling one day with theory classes and another day of practical work with no thought to the order is like putting all the exposition in one scene. You might imagine my response to mindless centralised timetabling!