The road ahead...

I've delayed my planned post for this week. The outbreak of anti-immigrant protests across the country, ostensibly a response to the tragedy in Southport, marks a moment that can not be ignored.

Despite Labour's success in the recent UK General Election, rising support for the Reform Party is an ominous sign. Indeed for me, and I'm sure I'm not alone, the inescapable conclusion to be taken from the campaign is that we have five short years to prepare for /prevent a significant lurch to the hard right in the next election.

Personal politics aside, this is a matter of professional ethics. As facilitators, drama teachers, and theatre directors our work centres on dialogue - the creation and performance of stories; stories that ask questions and the questioning of stories we are told. We create narratives that explore different perspectives and challenge the status quo. In doing so, we promote creativity, critical thinking and encourage open, inclusive discussions.

A politics of polarisation - which the populist right relies upon - is fundamentally anti-dialogical. The strategic sowing of division and mistrust undermines the very foundation of our work. It seeks to shut down conversations, create 'us vs. them' mentalities, and replace nuanced understanding with simplistic, often harmful narratives.

This is how it is. And it is likely to dominate our professional efforts for some time.

Yes, this is a learning moment, but not one in which we do the teaching and claim superiority by labelling the “bad 'uns”, tit-for-tat is a circular game. Proscription and prescription are equally coercive when handed down, and, in the end, just as impotent.

No, this is our learning moment, learning to recognise the possibilities and limitations of our practice and through recognition to innovate, invigorate and inspire authentic dialogue. To do nothing is to work hand in hand with those that seek to sow division. Our contributions may be modest, they may be bold, but they must be intentional. The struggle is in the centre ground. Those at the extremes are likely beyond persuasion, but they are few. How do we open our practice to make 'calling in' to dialogue more attractive than 'calling out' for a fight? How might we construct the theatre, the place to view or theorise about the events of this summer?

For my part, I will maintain a thread on this issue in future posts. I will also be offering workshops on facilitating controversy in the autumn - please let me know if you're interested.

In the meantime, I've included below a paper I wrote in 20171 linking anti-immigrant sentiment with displaced frustration theory, inequality, and low levels of social trust. It was written as an academic piece, with all the concomitant conventions, so it might seem somewhat dense compared to my normal posts.

These aren’t the targets you’re looking for…

Inequality, Displacement and Anti-immigration hostility

Missena:

The common people

Have little fondness for abstraction, and

Are eager to discover blame for our

Financial woes in some familiar cause,

With mouth and ears and arms and legs, in short

A person we might meet on any street.

(Brecht, 1938, Act1 Scene1)

Thus states the chief minister of the island state of Yahoo in Bertolt Brecht’s 1938 play ‘Round Heads and Pointed Heads’. A loose adaption of Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, the play recounts how the island’s elite, faced with the possibility of social unrest due to rising inequality, uses the far right Iberin Alliance to stimulate conflict between the nation’s two ethnic groups – those with pointed heads (Ziks) and those with round heads (Zaks):

Missena:

So instead of class war cleaving rich from poor

There's war between the Zaks and Ziks(ibid)

In the ensuing conflict, all elements challenging the dominant class structure are eliminated and the play ends with the corporate elite returning to ‘save’ the nation from the extremes of the Iberin Alliance. Initially written as an anti-Nazi satire, the play neatly encapsulates the now widely recognised phenomena of the deliberate initiation of inter-ethnic strife as a political strategy of divide and rule.

Particularly prevalent within, though not exclusive to, colonial contexts, the divide and rule strategy ferments internecine antagonism to interrupt the possibility of collective action against the dominant political power (Alder & Wang, 2014). The result is what Horowitz (1973, p. 1) refers to as ‘displaced’ rather than ‘direct’ ethnic aggression. Drawing on Berkowitz’s (1969) work on frustration-aggression theory2, Horowitz delineates between aggression that is directed at the source of frustration (direct) and that which is directed at some other, potentially innocent, party as a substitute target (displaced). Thus the divide and rule strategy is used by a dominant power to redirect anger that might be more accurately targeted at itself and displaces this aggression onto a more politically advantageous target. The success of the displacement hinges on the existence of factors that inhibit the expression of anger against the actual source of frustration. Simply put, if the level of inhibition (i.e. fear of state apparatus of control) exceeds the level of the aggrieved group’s anger the aggression is likely to be displaced onto a substitute target that offers lower levels of inhibition (ibid: p.4). Furthermore, if consciously desired by the dominant elite, this displacement may be amplified by the use of propaganda, false flag attacks and the exploitation of existing, though not necessarily salient, horizontal grievances3. However, Horowitz and Alder & Wang each predicate their analysis on specific assumptions. In Horowitz’ case it is that the aggressor recognises the existence and causality of the frustrating agent but is too inhibited to resort to direct aggression. Alternatively, Alder & Wang focus exclusively on the conscious and deceptive use of displacement by governing elites to consolidate their power. In this paper I intend to argue that a third combination exists, whereby the identity of the frustrating agent is not known and the resulting ethnic aggression is unconsciously displaced in a manner that ultimately acts against the interest of the aggressor. In the case I will be presenting the frustrating agent is income inequality and the substitute target, immigration.

Immigration is among the defining issues of our time. For over five years, since June 2010, UK voters have ranked immigration a close second to the economy (and ahead of health) as the ‘most important issue facing the country’.

(Hansen, 2016, p. 1)

Concerns about immigration have been a salient feature of social and political discourse in Britain since the Second World War (Paul, 1997)(McLaren & Johnson, 2004). Whilst the post war period was dominated by a political desire to maintain vestiges of empire on the one hand and a desperate shortage of labour on the other, later waves of immigration were driven by post-colonial impacts4 and then latterly the 2004 and 2007 enlargements of the European Union (ibid). Anti-immigration sentiment has found expression in number of forms from waves of race riots (1948, 1958, (Fryer, 1984)) to the emergence of nationalistic right wing parties ranging from the extreme to the increasingly mainstream (Dennison & Goodwin, 2015). As a result attitudes to immigration policy have become increasingly salient in British elections (Crawley, 2005; McLaren & Johnson, 2007) and most recently played a significant role in the 2016 United Kingdom European Union membership referendum (Goodwin & Heath, 2016). A large body of theory and analysis has been developed in an attempt to identify and understand the causation of this resentment in the interest of both social cohesion and the economy (Ruist, 2016). It would be simple to assume, utilising Horowitz’ method above, that in most cases antagonistic attitudes to the arrival of people from overseas are an example of direct aggression, in that incomers thwart the indigenous individual’s goal of prosperity by competing for employment and/or accepting lower remuneration. If this is the case then it could be expected that where migrant workers are generally engaged in unskilled or low paid work, anti-immigration sentiment would be strongest amongst those who work in the same sector, are low paid or who are unemployed. However, in a 2007 study, drawing on the 2003 British Attitudes Survey, McLaren & Johnson found that whilst 47% of respondents agreed that ‘Immigrants take jobs away from people who were born in Britain’ there was no statistically significant correlation between individual resource level factors and attitudes to immigration (p.721). Furthermore, being unemployed, or more generally in receipt of benefits also, made little or no difference to the probability of anti-immigration hostility5. This lack of correlation to individual self-interest echoes the finding of an earlier report for the Centre on Migration, Policy and Society:

[The] evidence suggests that - contrary to frequently expressed opinion - hostility towards immigrants including asylum seekers is linked neither to individuals’ experience of unemployment nor to local economic conditions.

(Crawley, 2005, p. 15)

It should perhaps be noted that both studies cited here precede the economic downturn of 2008/9. Could it perhaps be the case that current attitudes, most specifically those that informed the divisive discourse that surrounded the EU referendum, are a direct result of the effects of the downturn and the policy of austerity that followed? This would not appear to be the case as later studies suggest a continuing pattern:

Empirical results indicate that, contrary to expectations, the regional unemployment rates for natives and immigrants are not statistically associated with a higher or lower probability of expressing concerns over the impact of immigration or of preferring that no immigrants be allowed to come to the UK.

(Markaki, 2012)

McLaren and Johnson do find stronger correlations, however, between the perception of immigration posing a threat to indirect group resources and subsequent hostility (2007, p. 723). The analysis suggests that many whose personal interests are not impacted by competition for employment, benefits etc. develop anti-immigration sentiments in response to the perception of the risk to society as whole. Furthermore, the study also finds statistically significant evidence that symbolic concerns surrounding social identity and values6 are closely correlated to hostility to immigration (ibid, p.724). Finally, a notable relationship was found between a desire to end or restrict immigration and the perception that immigrants increase crime rates. Given that crime rates had, at the time of survey, fallen to all time low (Simmons & Dodd, 2003), McLaren and Johnson suggest these concerns, like those surrounding identity and values, are largely symbolic in nature (2007, p.717).

However, the British Attitudes Survey, on which the study relies, uses the terms ‘immigration’ and ‘immigrants’ somewhat loosely and it is unclear whether the respondents are referring to long term immigration, short term migration or refugees and asylum seekers. Blinder (2015) argues that what such surveys measure is in fact a concept of ‘imagined immigration’ a term that captures:

… unstated understandings among members of the public of what the word ‘immigrants’ means, and who it represents. Survey respondents call upon mental images of immigrants to help them make sense of questions about immigration, so that they can provide the responses to survey questions that ultimately make up public opinion.

(p.80)

Thus it is unclear whether, for example, the perceived threat to group-level resources such as employment comes from long term settled immigration or the presence of asylum seekers (who in any case cannot work), or whether concerns about immigration leading to increased crime are predicated on the activities of temporary economic migrants or the arrival of refugees. The lack of specificity adds further weight to the delineation between actual threats to self-interest and the more indirect or symbolic threats to group level resource, identity, values and freedom from crime. It is notable that whilst immigration (both economic migration and asylum) was a major issue in the Brexit campaign ultimately:

Of the twenty places with the fewest EU migrants, fifteen voted to leave the EU. By contrast, of the twenty places with the most EU migrants, eighteen voted to remain. In many of the areas that were among the most receptive to the Leave campaign there were hardly any EU migrants at all.

(Goodwin & Heath, 2016, p. 329)

The picture that emerges therefore is neither direct nor simple displaced aggression but instead what Horowitz (1973) identifies as cumulative aggression:

…that is, aggression produced by the conjunction of different sets of frustrations or grievances but directed at fewer than all of the frustrating groups.

(p. 5)

Nevertheless, the effect of these indirect and symbolic anxieties are profound and a question remains. If, in most cases, it is not immigration alone that is causing the broad insecurity regarding identity, values and the sense that ‘we have lost control of the country’, what is the cause and why is hostility not aimed at it directly?

Income Inequality in the UK

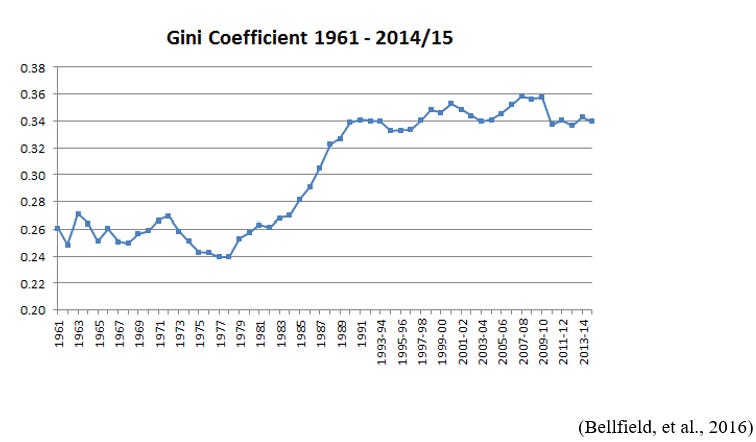

Between 1961 and 2010, income inequality in the United Kingdom as measured by the Gini Coefficient increased from 0.26 to 0.36, a rise of 38% (Bellfield, et al., 2016). The level of inequality dropped7 after the ‘Great Recession’ settling at 3.4 in 2014/15. However, it should be noted that inequality scores calculated from survey data may not accurately capture the level of top incomes and a recent study that uses income tax data to compensate for this flaw suggest the actual Gini coefficient should be approximately 5% higher (Jenkins, 2016). Nevertheless, even without taking these methodological flaws into consideration, in 2013 the UK ranked as the seventh most unequal country of the 30 members of the OED and the fourth most unequal in Europe (Inequality Trust, 2017).

There is a growing body of evidence that suggest income inequality can have a significantly deleterious effect on the way members of a society interrelate with one another and furthermore negatively impacts the maintenance and/or development of social capital (Uslaner & Rothstein, 2005; Pickett & Wilkinson, 2010; Vauclair & Bratanova, 2017). The cross national evidence suggests a strong negative correlation between inequality and levels of trust within a society. Uslaner & Rothstein (2005) identify two main types of trust relationships - particularised trust, wherein groups within a society act in line with narrow definitions of self interest, and ‘generalised’ or ‘social’ trust which in contrast links:

… us to people who are different from ourselves, it reflects a concern for others, especially people who have faced discrimination and as a result have fewer resources.

(p.45)

In societies with low levels of inequality citizens can identify with a shared sense of fate, recognising common outcomes and importantly view social and economic progress as delivering positive outcomes for all. By comparison, in highly unequal societies there is an acutely awareness that destinies are not shared. In such societies citizens may live in close proximity but lead radically dissimilar lives, experiencing vastly different forms of employment, education and healthcare (or in the case of the poorest, accessing none of these at all). In these circumstances, argue Uslaner & Rothstein, people develop high levels of particularised trust, adopting a position of narrow self-interest in a, perceived, competition against ‘others’ who, by virtue of this zero sum game, can only wish to lessen our prosperity or quality of life (ibid. p. 46). Consequently rather than seen as a simple correlation it is suggested that a causal relationship exists, that inequality results in erosion of social trust, an argument that is supported by the empirical evidence (ibid. p.70).

If as suggested above, low levels of social trust lead individuals to pursue narrow self-interest they must also presume that any differing expression of interest, identity or values to be in diametrical opposition to their own aims – difference is in essence a form of attack. Thus, the position of all within a society with high levels inequality8 becomes one of perpetual defence in which a pessimistic view of the future is the only logical position to take. As Uslaner & Rothstein conclude:

…optimism about the future (which is a key determinant of social trust) makes less sense when there is more economic inequality. When people believe that the future looks bright, trusting strangers seems less risky.

(ibid p. 51)

But if the future doesn’t look bright, as is the case for most within a highly unequal society, trusting strangers may feel like a very risky proposition. It is no surprise therefore, that a number of studies (Hummelsheim, et al., 2011; Vauclair & Bratanova, 2017 ; Vieno, et al., 2013) have found clear correlations between inequality and fear of crime:

…the finding suggests that fear of crime is triggered not just by actual levels of violence but by a system of income differences that fosters beliefs that violence is a likely and viable route to make up for status deprivation.

(Vauclair & Bratanova, 2017, p. 235)

Hence, the feelings of vulnerability and suspicion that are fostered by an unequal society reside in an assumption that given the limited legal opportunities to gain resource or social status ‘others’ are likely to resort to illegal means to do so. It is notable that this assumption exists irrespective of the actual crime rates (ibid). Furthermore Vauclair & Bratanova also found that within areas of high inequality ethnic majorities report a much higher fear of crime than ethnic minorities. This could, of course, suggest that the ethnic majority fears are based on experience, that in fact ethnic minorities (immigrants included) commit proportionally more crimes. However, in a Europe wide analysis, Ceobanu (2010) found no connection between the level of crimes committed by immigrants and public views about the effect of immigration on crime rates. What is left as cause is that this fear is a form of prejudice but as Wilkinson and Pickett (2010) argue this should be seen less as a moral failing and instead, as the evidence suggests, more as a symptom of inequality, a response to a hierarchal structure in which status is more readily achieved by placing ‘others’ below than by the, almost impossible task, of climbing higher oneself.

If by its very nature, income inequality infers the negative well-being of the majority and has such a fundamental impact on the fabric of society, a simple question arises: ‘Why, in a democratic society, does the oppressed majority not use the political means available to them ensure the existence of policies that redress the imbalance?’. This question, however, relies on two flawed premises. The first assumes that the chain of causality is both visible and comprehendible, when it is in fact abstract and complex. The second depends on the citizen’s belief that engagement with political institutions can actually bring about change. But, as Uslaner (2002) argues, high levels of particularised trust leads not only to competitive alienation of rival groups but to an equally detrimental level of ‘othering’ and suspicion with regard to social and political institutions. Within this worldview, political institutions exist to help ‘them’ and never ‘us’. Thus, to reframe the argument in terms of the frustration/aggression theory discussed above, inequality thwarts not only an individual’s pursuit of economic goals but also, via secondary effects, leads to a loss of social trust and raised levels of particularised trust. This increase in turn jointly influences perceptions of threat to identity, seeing one’s values in competition with others, and produces feelings of vulnerability to crime, both of which impede the individual’s pursuit of wellbeing and security. The resulting frustrations lead to aggression, but given that inequality offers little in the way of a direct, cognizable target these cumulative frustrations result in an aggression response that is unconsciously displaced upon the ultimate ‘other’ – the immigrant. After all in a world of particularised trust, to return to Brecht’s lines that opened this paper, the people…

Have little fondness for abstraction, and

Are eager to discover blame for our

Financial woes in some familiar cause,

With mouth and ears and arms and legs, in short

A person we might meet on any street.(Brecht, 1938, 1:1)

Bibliography

Alder, S. & Wang, Y., 2014. Divide and Rule: An Origin of Polarization and Ethnic Conflict, Zurich: University of Zurich.

Bellfield, C., Cribb, J., Hood, A. & Joyce, R., 2016. Living standards, poverty and inequality in the UK: 2016, London: Insititute for Fiscal studies .

Berkowitz, L., 1969. The frustration-aggression hypothesis revisited. In: Roots of aggression. New York: Atherton Press.

Blinder, S., 2015. Imagined Immigration:The Impact of Different Meanings of ‘Immigrants’ in Public Opinion and Policy Debates in Britain. Political Studies , Volume 63, pp. 80-100.

Brecht, B., 1938. Round Heads and Pointed Heads. London: Methuen.

Ceobanu, A., 2010. Usual suspects? Public views about immigrants’ impact on crime in European. International Journal of Comparative Sociology , 52(1), pp. 114-131.

Crawley, H., 2005. Evidence on Attitudes to Asylum and Immigration: What We Know, Don’t Know and Need to Know, Oxford: Centre on Migration, Policy and Society.

Dennison, J. & Goodwin, M., 2015. Immigration, Issue Ownership and the Rise of UKIP. Parliamentary Affairs, 68(1), pp. 168-187.

Fryer, P., 1984. Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. London: Pluto Press.

Goodwin, M. J. & Heath, O., 2016. The 2016 Referendum, Brexit and the Left Behind: An Aggregate-level Analysis of the Result. The Political Quarterly, 87(3), pp. 323-332.

Hansen, R., 2016. Making Immigration Work: How Britain and Europe Can Cope with their Immigration Crises. Government and Opposition, 51(2), pp. 183-208.

Horowitz, D. L., 1973. Direct, Displaced, and Cumulative Ethnic Aggression. Comparative Politics, Oct, 6(1), pp. 1-16.

Horowitz, D. L., 2000. Ethnic Groups in Conflict. Berkeley: Univeristy of California Press.

Hummelsheim, D., Hirtenlehner , H., Jackson, J. & Oberwittler, D., 2011. Social insecurities and fear of crime: A cross-national study on the impact of welfare state policies on crime-related anxieties. European Sociological Review , 27(3), pp. 327-345.

Inequality Trust, 2017. The Scale of Economic Inequality in the UK. [Online]

Available at: https://www.equalitytrust.org.uk/scale-economic-inequality-uk

[Accessed 21 March 2017].

Jenkins, S. P., 2016. Pareto Models, Top Incomes and Recent Trends in UK. Economica.

Keefer, P., 2010. The Ethnicity Distraction? Political Credibility and Partisan Preferences in Africa, s.l.: s.n.

Markaki, Y., 2012. Sources of anti-immigration attitudes in the United Kingdom: the impact of population, labour market and skills context , Colchester: Institute for Social and Economic Researc.

McLaren , L. M. & Johnson, M., 2004. Understanding the Rising Tide of Anti-Immigrant Sentiment. In: J. C. K. T. C. B. a. M. P. A. Park, ed. British Social Attitudes, 21st Report.. s.l.:s.n., pp. 169-200.

McLaren, L. & Johnson, M., 2007. Resources, Group Conflict and Symbols: Explaining Anti-Immigration Hostility in Britain. Political Studies , 55(4), pp. 709-732.

Paul, K., 1997. Whitewashing Britain: Race and Citizenship in the Postwar Era. Ithaca,NY: Cornell University Press.

Pickett, K. & Wilkinson, R., 2010. The Spirit Level. 2nd ed. London: Penguin.

Ruist, J., 2016. How the macroeconomic context impacts on attitudes to immigration: Evidence from within-country variation. Social Science Research, Volume 60, pp. 125-134.

Simmons, J. & Dodd, T., 2003. Crime in England and Wales 2002/2003, London: Office for National Statistics.

Uslaner, E., 2002. The Moral Foundations of Trust. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

Uslaner, E. M. & Rothstein, B., 2005. ALL FOR ALL Equality, Corruption, and Social Trust. World POlitics, 58(1), pp. 41-72.

Vauclair, C. M. & Bratanova, B., 2017. Income inequality and fear of crime across the European region. European Journal of Criminology, 14(2), pp. 221-241.

Vieno, A., Roccato, M. & Russo S, 2013. Is fear of crime mainly social and economic insecurity. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23(6), pp. 519-535.

It is important to note that whilst the paper is now seven years old, recent research continues to disprove the link between crime rates and immigration:

Kubrin, C.E., Luo, X.I. and Hipp, J.R., 2024. Immigration and Crime: Is the Relationship Nonlinear? The British Journal of Criminology, p.azae045. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azae045.

Tufail, M. et al. (2022) ‘Does more immigration lead to more violent and property crimes? A case study of 30 selected OECD countries’, Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 36(1), pp. 1867–1885. doi: 10.1080/1331677X.2022.2094437.

The hypothesis that aggression emanates from anger produced when some form of goal oriented behavior is thwarted (Berkowitz, 1969).

Essentially utilising/amplifying existing direct aggression to subsume unrelated issues.

For instance the influx of commonwealth citizens exiled from Kenya (1968) and Uganda (1972) following political crises in those countries (Paul, 1997).

McLaren & Johnson also point out that this replicates similar findings in the US and Europe (2007, p.722)

Though it should perhaps be noted that the survey questions used in the analysis referred exclusively to immigrants who are Muslim.

Though it should be noted that this drop was a result of reduced income in some of the upper quartiles rather than increased income in the lower quartiles (Bellfield, et al., 2016)

With perhaps the exception of the very top end of the income hierarchy.