The Weak Suffer What They Must?

Reading power on and off the stage

You know as well as we do that [what is right] is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War

Many drama groups, youth theatres and classes are starting back this week.

They are doing so after a fortnight that has felt, for many, quietly destabilising. Headlines have arrived thick and fast – raids, killings, territorial threats, abrupt policy shifts – delivered with a performative confidence that leaves little room for explanation or pause. Even for those of us living far from the United States, something has shifted. Not necessarily in what people know, but in what they feel is possible.

Most engagement with these events is at headline level. Few participants will arrive ready to debate detail or policy. But atmospheres travel. Certainty, bravado, fear, cynicism. These things seep into sessions long before anyone names them.

Anyone working with groups will recognise this subtle dynamic. Participants aren’t looking for answers. They’re looking for cues:

How are others responding?

Is this something to joke about, to ignore, to be anxious about?

Is cynicism the safest stance, or is earnestness still allowed?

Over the break, like many, I spent a lot of time with children - too young to follow world affairs closely, but old enough to pick up that something was going on. They weren't repeating news stories; they were reading adult reactions.

Trying to navigate between different families' approaches to what children should or should not know, I ended up in conversations about power itself: why do people follow leaders others think are 'bad'? How does lying actually work as a tactic? Why does confidence persuade even when someone might be wrong?

None of this required political expertise. It required an ability to recognise how power is being performed.

Learning to read power

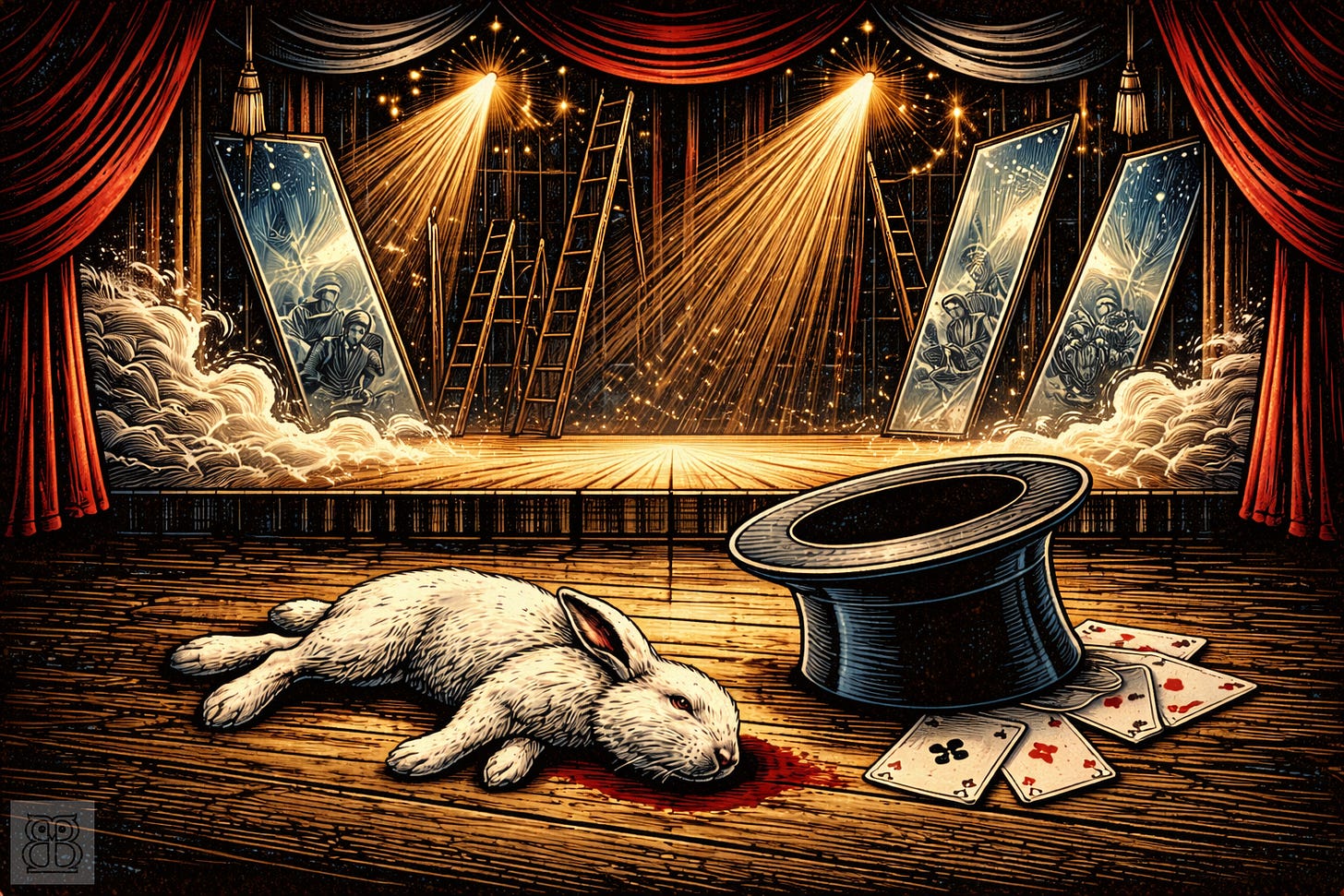

For many drama practitioners, Keith Johnstone’s status work from Impro feels familiar – almost too familiar. We think we know it. And because of that, we often stop really seeing it. Out come the playing cards held to the forehead. A quick pass of the duchess and the tramp on the street. The exercise is done.

Returning to Johnstone with more experience under your belt can be quietly unsettling, because it reveals how much gets flattened or misremembered.

Status work does not ask whether a character deserves power, or whether a leader is legitimate. It asks something simpler and more unsettling: what is happening, moment by moment, that makes others defer, comply, resist or laugh?

Status, in this sense, is not a fixed attribute. It is a live transaction. It rises and falls through pace, stillness, interruption, reaction - through who names the situation, and who waits to see how it will be named.

My favourite example are three teachers:

The compulsive high-status player. Every infraction is taken as a personal challenge. They shout, threaten, escalate. Pupils are often amused rather than cowed. These teachers frequently burn out early, sometimes literally – stress, heart problems, early retirement.

The compulsive low-status player. Keen to be liked, to be ‘down with the kids’, they offer warmth without structure. Lines blur. Boundaries dissolve. These teachers often leave under a cloud – not because they lacked care, but because they lacked authority.

The status expert - my old English teacher, Mr Callum. He never announced his authority, and never relinquished it either. He shifted status constantly – up, down, sideways – often without us noticing. He was warmly humorous, but there was a line you did not cross. He never needed to raise his voice; we were acutely aware that he could. His power came precisely from not having to play it.

Johnstone’s point was never that one should ‘play high status’. Quite the opposite. Power comes from recognising which status a situation calls for. Often, the status achieved is inverse to the status performed.

These patterns are not confined to classrooms. They are the same moves being performed at scale right now – compulsive high-status playing that looks like authority but is actually fragile and reactive, endlessly triggered by the slightest question or doubt.

The relief of the middle

Status work helps us read individual transactions. In a room, face to face, compulsive high-status playing is brittle. Teacher One can be derailed by anyone who learns which buttons to push.

But amplified through media, the same pattern becomes effective in ways that moment-to-moment transaction analysis cannot fully explain. This is where classical rhetoric becomes useful.

Aristotle identified three modes of persuasion: through logic (logos), through emotional appeal (pathos), and through the speaker’s credibility (ethos). That third mode does complementary work to status analysis. It helps explain how authority is constructed with audiences at scale, beyond the immediate room.

According to Aristotle, persuasive ethos requires three qualities. The first is aretē – often translated as ‘virtue’, but more accurately meaning the values your audience admires. As Jay Heinrichs makes explicit, this is not about universal moral goodness. It is about appearing aligned with what this audience sees as excellent.

This is crucial. Aggressive certainty, rule-breaking, ‘telling it like it is’ – these can function as rhetorical virtue if they match what an audience values.

Brecht’s Arturo Ui understands this perfectly. He does not present himself to the cauliflower traders as morally upright in any universal sense. He presents himself as someone who shares their values – protection, profit, getting things done when legitimate means fail.

Ui’s violence reads as strength to an audience that values decisive action over legal niceties.

The second quality is phronesis – practical wisdom. This is not obedience to rules. It is judgement about when rules need breaking.

Richard III demonstrates this ruthlessly. He knows exactly which conventions to violate, and when. To audiences who experience existing power structures as weak or corrupt, someone who violates those norms can appear to know what to do in this specific situation. What might otherwise read as recklessness registers as competence.

Heinrichs describes a rhetorical tactic that should feel familiar to anyone who has taught status: threaten the extreme, then occupy the centre.

By placing something drastic on the table – whether or not it is ever intended – the speaker makes a lesser course of action feel reasonable, even generous. The audience experiences relief, not coercion.

Arturo Ui is a master of this. He manufactures threats – fires, violence, chaos – then presents himself as the reasonable solution. Protection rackets operate on exactly this principle: create fear of the extreme, then offer the ‘moderate’ alternative of paying for safety. What is actually extortion appears as sensible self-preservation by comparison to the threatened violence.

Watch almost any press conference this week and you will see the same mechanisms at work.

Johnstone was right that there is no middle status in the moment-to-moment transaction. You are playing high or low. But rhetoric helps us recognise that what appears to be a moderate position – the relief of stepping back from the most extreme threat – can be deeply persuasive at population scale, even when the ‘moderate’ position is itself extreme.

This is where status work and rhetorical analysis work together. Status helps us read the fragility of compulsive high-status playing in the room. Rhetoric helps us understand why that same pattern, amplified through media, can be effective with audiences who are reading a different performance.

Characters who show us how it works

Drama has been anatomising this for a very long time.

Richard III’s power lies less in brute force than in his control of narrative and timing. Julius Caesar falls not because he lacks authority, but because others understand how to appear authoritative in his shadow. Even characters we meet early in our teaching lives – the gang dynamics of Blood Brothers, the shifting hierarchies of DNA – show how quickly groups settle into patterns of dominance and deference once fear or scarcity enters the room.

Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui is perhaps the most explicit example, not because Ui is a stand-in for any single contemporary figure, but because the play tracks how inevitability is manufactured. Threats are exaggerated. Fear narrows the field of acceptable responses. What once seemed unthinkable comes to feel like order.

The play’s final warning matters here. Ui may be defeated, but the womb he crawled from is still going strong.1 Not because history repeats itself mechanically, but because the conditions that make such performances effective – fear, fatigue, the longing for certainty – are easily recreated.

Drama does not show us villains. It shows us mechanisms.

Why this matters now

Participants returning to workshops this week are not arriving as analysts of world politics. They are arriving as sensitive readers of atmosphere. They are picking up cues about how seriously to take things, how much danger is in the air, whether mockery or compliance is the safer response.

What feels urgent, then, is not to supply conclusions, but to refresh our own fluency in recognising power play, so that it does not remain invisible or mystical.

What status work offers is not political analysis. It is perceptual training. When you teach someone to read status transactions through character work, you are building their capacity to recognise these same tactics elsewhere – on screens, in headlines, in performative certainty designed to shut down questions.

Johnstone’s status work and Aristotle’s ethos are not specialised political tools. They are simple adjuncts to how we already analyse scenes, characters and relationships. Used well, they do not tell anyone what to think. They make it easier to see what is being done – and how quickly ‘must’ can be made to feel natural.

The line “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must” is often quoted as though it describes an unchangeable law.2

But that’s frequently part of the performance itself - making force appear absolute when it isn’t. Getting people to accept the frame before testing whether it’s actually true.

Drama suggests otherwise. Not because recognising status play gives us the power to stop force – it doesn’t – but because it helps us refuse the claim that force is natural, inevitable, or as absolute as it presents itself to be.

The weak suffer what they must only once the frame has been accepted - and once the performance of inevitability goes unexamined.

Recognising the anatomy of power has always been part of our craft. Not as a consolation, but as a fundamental capacity.

I write the newsletter from various coffee shops, imagining I’m chatting with my subscribers over a cappuccino. So if you ever find an issue particularly helpful or thought-provoking, you can now literally buy me the coffee that will fuel the next one. This approach keeps the newsletter free and accessible for everyone while still allowing you to support the work when it resonates with you.

Sources:

Brecht, B., 1981. The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui. London: Methuen Drama.

Heinrichs, J., 2010. Winning Arguments: From Aristotle to Obama - Everything You Need to Know About the Art of Persuasion. London: Penguin Books.

Johnstone, K., 2007. Impro: Improvisation and the Theatre. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War (1989) The Complete Hobbes Translation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

From the epilogue to Bertolt Brecht’s The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui*:

“Learn how to see, not gape.

To act, instead of talking all day.

The world was almost won by such an ape!

The nations put him where his kind belong.

But don’t rejoice too soon at your escape

– the womb he crawled from is still going strong.”

The line is spoken by the Athenians in the Melian Dialogue, presented as a statement of how the world works. By the end of the Peloponnesian War, Athens itself would no longer occupy the position from which such statements could be made.