Who disagrees with Jo?

Principles to avoid it all kicking off #1

"I CAN'T BEAR TO TURN ON THE NEWS ANY MORE!" It's a cliché, of course. It's inaccurate, at least partially - who 'turns on' the news in the digital age! It is untrue, for me at least (though I often think it). But it is also, ultimately, futile.

Even if we escape the repetitive minutiae of the 24-hour news cycle (highly recommended) the big themes, the tensions, and the undercurrents find their way into our workshops. It's not just noise – it's the reality participants bring in with them. Whether the issues are explicitly named or lurking beneath the surface, difficult topics are going to come up. We need to be ready.

As I mentioned in my post after the riots in August, this is an inescapable question of professional ethics “but not one in which we do the teaching and claim superiority by labelling the bad 'uns: tit-for-tat is a circular game”.

No, even as past tragedies are weaponised for new agendas, and the slew of executive orders from Potus#47 cast the unmistakable shadow of authoritarianism, so the urgent need to commit our efforts, however modestly, to improving our participants' ability to engage in authentic dialogue. I'm not suggesting ditching this weekend's planned session on circus skills to debate the merits of a new global order. But you could quietly start to review how you deal with discussion, questions and answers in your sessions. Then when an inflammatory comment or divisive topic does arise the potential for dialogue can be harnessed more productively.

As a small contribution to this endeavour I would to share a set of practical principles to avoid discussions from becoming too heated. These were developed over a series of projects looking at anti-immigration sentiment 2015-2018 but can be applied in any context.

• De-personalise the issue, personalise the person,

• Define the issue,

• Deliberate: Keeping the discussion future-focused,

• Reframe the register.

I'll introduce each principle over a series of short posts interspersed with some longer pieces to explore the context and broader strategies for difficult discussions. I'll also add some links to sources where I discuss this work in more detail.

Principle #1

One way a discussion can go off track is when a participant feels that their personal values or self-worth, rather than the topic, have become the object of scrutiny. When this happens even the most simple counterargument can be misinterpreted as a judgement of character – the ‘right’ or ‘wrongness’ of the original point erroneously becomes ‘right’ or ‘wrongness’ of the person.

Jo: I think that people should have to take an exam before they are allowed to have children.

Facilitator: Who agrees with Jo?

No one raises their hand to agree with Jo

Facilitator: Ok. Hands up if you disagree.

Most of the class raise their hands to disagree with Jo

Facilitator: Ok. Alex, why have you got your hand up?

It doesn't matter what they say, "Alex- who disagrees with Jo" has now been framed as an antagonist which is unlikely to have gone unnoticed by Jo.

What if the facilitator had taken a different approach?

De-personalise the issue

Jo: I think that people should have to take an exam before they are allowed to have children.

Facilitator: Here's an idea. People should have to take an exam before they are allowed to have children.

Who can think of a possible advantage of there being some type of criteria to be met before becoming a parent?

Who can think of possible disadvantages?

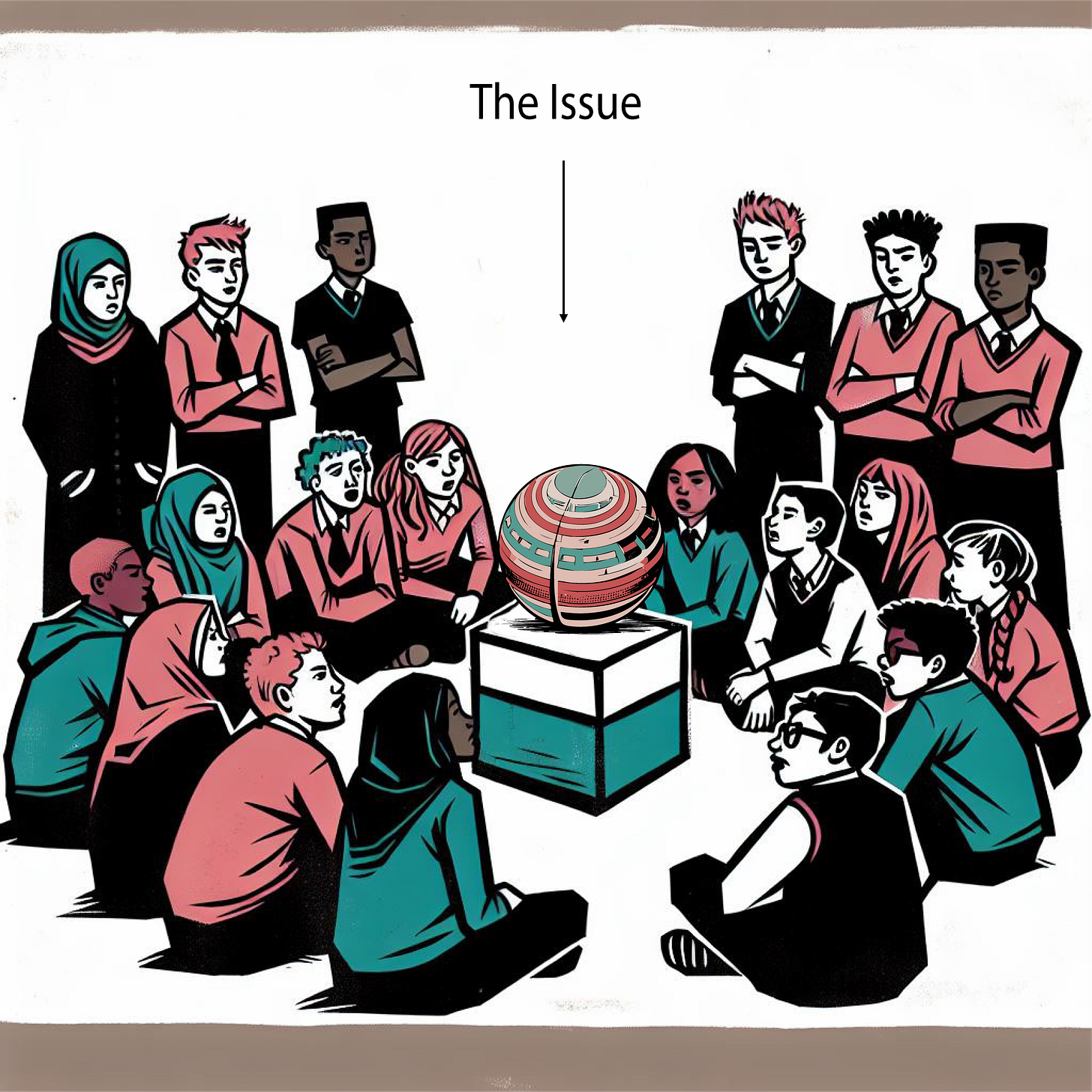

In this version the facilitator has very clearly separated the issue from the participant. The rest of the group are analysing the idea rather than passing judgement on the contributor. This act of naming the issue turns it into what Freire (1993) would call a ‘cognizable object’. Like its physical counterpart, the cognizable object exists independently of the person that names it.

Here’s another, real life, example:

Participant 1: I’ve lived here all my life, and now I don’t recognise a single face on the street…

Participant 2: (shouting out dismissively) Well why not try talking to people…

Participant 1: … or understand a bloody word… it’s not me that’s unfriendly.

This looks very likely to become heated1.

Facilitator: Positive interruption – Now here’s something… No wait – let’s take this out to everyone.

Turning the issue into a cognizable object – Something we haven’t spoken about yet is ‘isolation’.

Offering the object to the group as something to explore - Is it possible that, in the play, the character Pat, living in a busy area, might feel alone?

In this last example the facilitator turns the issue into something separate to the participants, an object that can be known, analysed and commented on. Furthermore, Participant 1 can see their issue accepted into the discussion whilst hopefully achieving some critical distance from it. Referencing the fictional character created within the drama is the ideal vehicle for creating even more distance. The play becomes an excuse, a proxy for the participant's own experiences2.

Personalise the person

Just as the issue becomes objectified care must also be taken to recognise the subjectivity of the participants. This is particularly true when statistics are quoted to disprove a contribution. Whilst data can be useful in contextualising fallacious claims, they should not be viewed as truth makers in themselves. It may be statistically true that only 0.5% of UK teenagers are involved in gangs but the lived truth of residing in a gang crime hotspot results in a very different experience.

Summary

The key takeaway here - discussions are for analysing and evaluating objects (ideas, concepts, things) rather than people3 - is deceptively simple. There may be some resistance. A participant may enjoy the status boost of 'their' idea being chosen, though it is to be noted that this joy exists in direct proportion to the number of those whose ideas were not agreed with. It can also be tricky to identify the cognizable object on the spot. Knowing it and doing it are different things but, as ever, it's just a matter of practice.

References:

Burns, B. 2018. The dynamics of disagreement: facilitating discussion in the populist age. Education & Theatre Journal, 19, 124-131.

Burns, B (2021). Dialogue is Fundamental: The Techne of Drama Facilitation. In Choleva N. (ed.) (2021). _"It Could Be Me – It Could Be You" - Drama/Theatre in Education methodologies and activities for raising awareness on human rights and refugees. Athens: UNHCR/TENet-Gr.

Freire, P., 1993. Pedagogy of the city. New York: Continuum.

Or the opposite: Frozen, whereby the interlocutors and the rest of the group decide not to 'go there' or indeed anywhere for the rest of the session. Neither outcome is good for participation.

There is, of course, an important place for expressing, honouring and exploring personal experience - but not in the situations described above

Essentially Martin Buber’s I-It vs I-Thou relations