Why Your Next Great Workshop Exercise Might Be One You've Used Before

Upcycling, Frame Casting, and Groundhog Day

SIX WORKSHOPS, SIX FACILITATORS, SIX DIFFERENT CITIES. And yet, every session began the same way - same three warm-up exercises, same sequence, same rhythms.

It wasn’t a template workshop. And it wasn’t a coincidence.

All six were professional practitioners on a work-based master's programme. A few weeks earlier, they'd shared an intensive study week in which each had taken a turn running a warm-up. No one was assessed. No feedback was given. But when I hit the road for workplace observations, the same three warm up exercises resurfaced time and time again.

At first glance, this looked like a textbook case of the availability heuristic: we're exposed to a new technique and find ourselves using it at every available opportunity.1 But why these three activities out of a week's worth of workshops? It's not that they were especially novel. The only common factor was that each was a variation of a well-known exercise with an innovative twist.

A new spin on an old favourite!

So perhaps these facilitators weren't just mindlessly copying. Maybe they had instinctively recognised the potential of using variations of the structures they were familiar with. New exercises take time to develop and 'bed-in', sticking with material that works is reliable but unlikely to yield new insights. Taking the structure of existing activities and adapting them to serve different purposes or achieve new outcomes offers the best of both worlds. There's some familiarity but also some 'strangeness' - enough to keep both facilitator and participants on their toes and sensitive to possibility. This is what made the three exercises stand out during the intensive week. The variations added a layer of sophistication, explicitly taking things up a level.2 These old favourites weren't recycled, they were upcycled!

Upcycling workshop exercises involves taking the core structure of a game and repurposing it for new objectives. It is not about discarding what's effective but rather about reimagining it. The core mechanics of the activity remain the same, but the objectives and framing shift to align with the specific goals of the workshop. Intention is key. A furniture 'upcycler' doesn't just tinker to see how things might turn out. They might see lots of possibilities in an old cast iron water pump but decide to turn it into a lamp stand. As I've discussed previously purpose comes first.

It makes much more sense to do your own upcycling. This is also the best way to avoid falling into the The Fast Food Seagull fallacy. I think it was this that made the exercise sequence jar in those six observations. The sequence didn't quite fit any of the specific contexts. It was close enough in some but distinctively mismatched in others.

I write this newsletter from various coffee shops, imagining I'm chatting with you. If you ever find an article particularly helpful or thought-provoking, you can now literally buy me a coffee to fuel the next edition. This helps keep the newsletter free and accessible for everyone.

An approach to Upcycling: Frame-casting

Exercises are complex. Not just complicated—complex. They sit at the intersection of multiple, overlapping systems. Spatial and physical constraints (walls, floors, gravity), material needs (chairs? props?), timing, narrative logic, motivational currents, participant intentions… even a game as seemingly simple as Stuck in the Mud contains far more variables than can be usefully listed. So how do we change one?

You can’t intentionally repurpose a complex system by just tweaking bits at random. Or rather—you can, but you won’t know what the outcome means. The only way to shift things meaningfully is to simplify. Not by dumbing down, but by casting the complexity into a conceptual framework. I’m calling this frame-casting.

To frame-cast an exercise is to locate it in a framework that reduces the variables in play and opens up new pathways for purposeful change. The frame lets us ask “what if…” without being overwhelmed by the infinite branching of possibilities.

Take Stuck in the Mud. Casting a spatial frame reveals players are standing, moving independently in an open space. But what if ? What if we restrict movement to a circle? What if it becomes a seated game? What if players are tethered in pairs? A whole new set of exercises begin to emerge—and crucially, we understand why they emerged, and what we’re testing.

I’m currently developing a short course and future post that dig deeper into frame-casting, but the two most useful for upcycling are the “Struggle Frame” and Clive Barker’s Theatre Game Categories. For now, I’ll outline how these two frames can help reimagine even the most familiar exercises in the sections below.

Upcycling Example: Splat!

Splat is a classic drama game. I must confess I'm not a big fan myself, but it's practically ubiquitous and probably the one exercise I can confidently assume everyone knows.3

For those unfamiliar: the group stands in a circle with the facilitator in the centre. In free-flowing turns, the facilitator points at a participant while loudly saying 'Splat'. The participant must duck before the participants either side turn inwards to launch an imaginary custard pie while simultaneously shouting 'Splat'. It's often played as an elimination game, with anyone not ducking or splatting quickly enough being knocked out, leading to a final duel between the last two players.

1: Purposeful Upcycling

It's a weekly drama club. The longstanding older core of the group have moved on, and new members have joined. The group don't seem to be gelling and there is a sense of positioning/jostling for status.

You decide to make the secondary aim of the forthcoming workshop: To build group cohesion

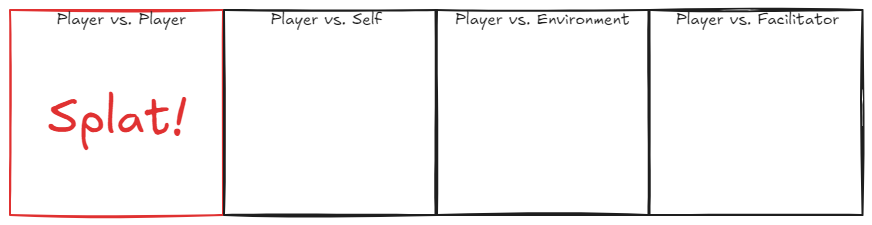

You use the Struggle (or Agon) frame. This identifies the protagonist and antagonist of the exercise. For instance, you might have:

Players against Players - using competition as motivation

Players against Facilitator - The group working together in response to challenges created by the facilitator.

Player against environment - overcoming gravity or physical obstacles

Player against Self - challenging/improving own abilities.

Casting Splat into the Struggle Frame reveals it as a Player vs Player game (though if the elimination aspect is omitted it can also function as Player vs Self).

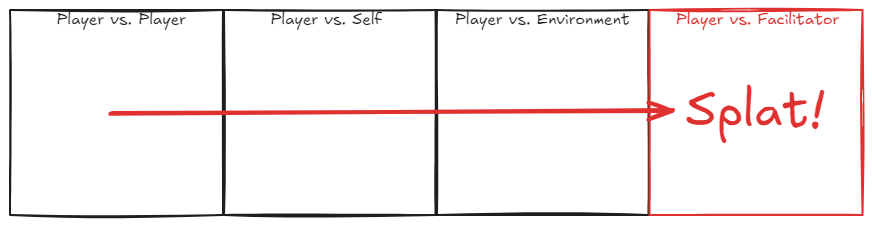

But what if: Splat were upcycled as a ‘Players vs Facilitator game’? Might this be a way of getting the group to work together for a common goal?

Upcycle as... Splat Back:

Group stands in circle.

Facilitator as the splatter (makes splatting motion rather than pointing).

Splattee ducks (as before).

Participants either side send a splat back at the facilitator whilst simultaneously shouting "Splat Back".

If the splattee ducks in time and the 'splatback' is simultaneous the group wins. If not, the facilitator wins that round.

No elimination but a facilitator vs group scoring system could be added or a simple count of how many consecutive splat backs are successful and try to improve each session.

2. Exploratory Upcycling

Your group loves playing Splat, but you want to shake things up for next term.

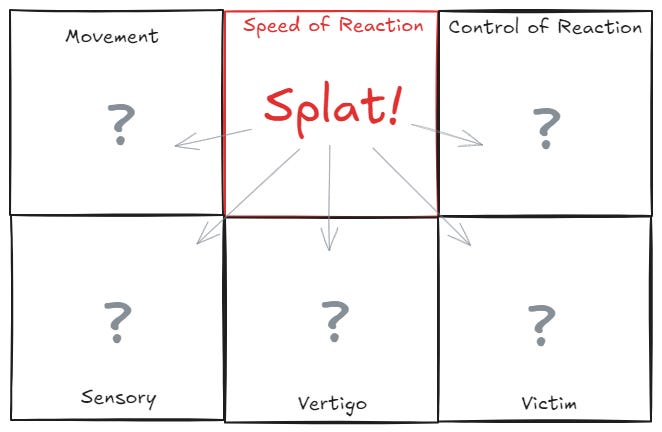

You frame-cast using Clive Barker's Theatre Games. This is a taxonomy based on the intention and mechanics of the exercise:

Movement: Freeing energy from the constraints of social conditioning and self-consciousness.

Speed of Reaction: Quick decision-making and responsiveness.

Control of Reaction: Managing actions and responses.

Sensory Exercises: Enhancing perception through sight, sound, touch, etc.

Vertigo Exercises: Deliberately disrupting perceptual stability

Victim Games: Placing someone in a challenging position against the group.

Splat is conventionally a Speed of Reaction exercise. But what if we cast it into other categories for inspiration?

Splat as:

Movement: Change the movement motifs to something more complex or challenging. Instead of elimination the last one to complete the movement has to run around the outside of the circle.

Control of Reaction: Instead of pointing at a splatee, call them by number in the circle (i.e Splat 3). Create a forfeit for anyone who moves when it's not their turn.

Sensory Exercise: Participants have eyes closed. Facilitator moves around outside of circle and stage-whispers 'Splat' to Splatee who claps and ducks while those on the either side shout splat and clap (probably best they don't turn with outstretched arms)

Vertigo: Nothing springs immediately to mind!

Victim: Something whereby the splattee is is 'splatted' by the rest of the group - perhaps with some kind of pressure to get it right or become the splatee.

There's something interesting in the last one which relates to some ideas I've had about exploring peer pressure and cancel culture.

Upcycle as...Pile On!

Turning splat into a victim game to explore "pile-on" culture on the internet.

*Warning to self: victim games should always be used with great care particularly ensuring the exercise contains appropriate measures by which the facilitator can control the pressure placed on any specific individual. Knowing the group well enough to make this judgement is key *

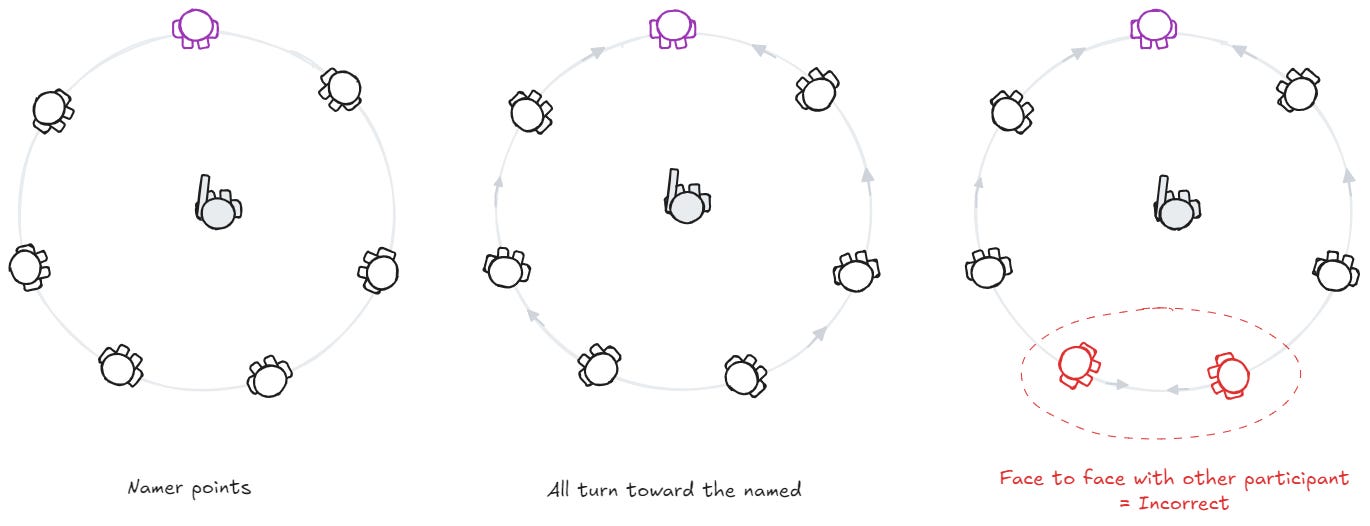

Basic Structure

Group stand in a circle.

The Namer stands in the middle - (must always be the facilitator)

The Namer identifies a participant (The Named).

The rest of the group turn to face the Named and complete an action.

Name and Fame - Warm up rounds

Namer gestures with an open hand and calls the Named's name affectionately

Participants turn towards Named, applauding and calling out their name

If Namer spots an incorrect move (someone turning to face another participant) they 'name' one of them with an affectionate "Ohh (name)".

Participants turn and repeat "Ohh (name)"

If Namer spots another incorrect move, repeat above. Otherwise, begin again.

Name and Shame - Main round

Namer points at participant accusingly say "You!"

Participants turn towards Named, pointing and accusingly saying "You"

If Namer spots an incorrect move (someone turning to face another participant) they accuse one of them with a shocked "You!".

Participants turn point and repeat "You!"

If Namer spots another incorrect move, repeat above. Otherwise begin again.

I'm not sure how, but I'd be looking for ways to keep it moving swiftly with occasional pauses. Maybe add variation where those in an incorrect move can accuse each other. Or add participants shouting "You!" in canon to add to 'pile on' feel.

Post-exercise discussion explores the experience of being called by name versus "You!", the pressure to avoid mistakes, and the contrasting feelings of being accused versus being an accuser.

Note: I undertook this upcycling process in real-time, demonstrating how frameworks can generate new possibilities from familiar structures. However, this particular variation would require further development and careful consideration before implementation.

Final thoughts..

No one wants their practice to gather dust. But neither do we want to continue the exhausting hunt for yet another edition of '100 Drama Games to...'?

The practice of upcycling is our way out of that false dilemma. It’s how we transform those familiar, reliable structures into fresh experiences. That simple process - 'frame-casting' to reveal the possibilities of the activity, and then testing your iterations - can be more than just a technique; it could be a mindset shift.

The key insight from those six identical warm-up sequences wasn't that the facilitators lacked creativity, but that they had recognised something valuable in exercises that balanced familiarity with novelty. When we upcycle thoughtfully, we create activities that feel both comfortable and surprising, keeping participants engaged while serving our workshop's specific goals.

Most importantly, upcycling encourages us to look more deeply at the exercises we already know. Every familiar game contains multiple potential applications waiting to be discovered through intentional reframing. In a profession where we're constantly seeking new material, perhaps the richest resource is the one we've been using all along - we just need to learn to see it differently.

Sources:

Barker, C., 1995. Theatre games: a new approach to drama training. Reprint edn. A Methuen paperback. London: Methuen.

Facilitators are constantly on the look out for new material. Type 'Drama Games Book' into a search engine and you'll find umpteen versions of '100 games to...' - though you then have to take the time to read them. But, experiencing a new exercise first hand instantly triggers our inner magpie - 'I'll have that!' - leaving it at the forefront of our mind next time we're rooting around for a new idea. We end up using it for everything for a couple of weeks and if it turns out to be useful it becomes part of our repertoire.

A core theme of the masters program was to 'take your practice to the next level'. This may explain why these exercises found themselves in everyone's observed workshop.

In fact I once had to ban a group of student facilitators from using Splat (or any upcycled variations) for the sake of all involved. They know who they are!